A Revolution on Screen, Pt 2

"A Revolution on Screen" is a two-part video essay coinciding with the 2009 New York Film Festival Masterworks series "(Re)Inventing China: A New Cinema for a New Society, 1949–1966." This series is the first major U.S. retrospective of the films made during the "Seventeen Years" period between the establishment of the People's Republic of China and the Cultural Revolution. Part 1 can be viewed here.

When the Communist Party founded the People's Republic of China in 1949, they harnessed the power of cinema to captivate the masses. But only a fraction of Chinese had even seen a movie, so stories had to be simple in concept and straightforward in execution to ensure widespread appeal. To achieve this, Chinese filmmakers embraced both Soviet socialist realism and Chinese opera traditions, while avoiding the individual and psychological preoccupations of Hollywood movies.

But over the course of the 1950s, Chinese audiences grew in size and became more familiar with films. They became less responsive to the conventions of Maoist propaganda movies. Even the hardliners could not ignore the need to keep the masses engaged by bringing variety and freshness to the same messages. Gradually new genres began to emerge, in some ways corresponding to their Hollywood counterparts.

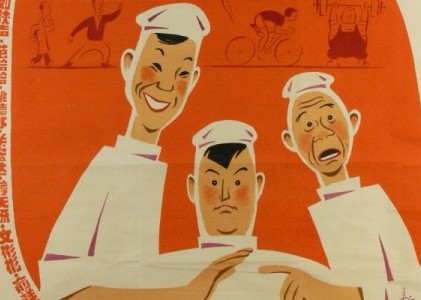

Comedies like Xie Jin's Big Li, Little Li and Old Li (1962) allowed for social agendas to be promoted in an amusing, soft-sell manner. Big Li, Little Li and Old Li pushes for physical-fitness programs to be implemented at factories across the country, so that workers are healthier and thus more productive. The film succeeds as both comedy and propaganda because it acknowledges and exploits the inherent awkwardness brought by change, especially among older, more resistant workers. What's also fascinating is the film's stylistic innovations; watching it, you'd think that Xie Jin had been studying his contemporary Frank Tashlin from across the Pacific, even though Hollywood films were still banned in China.

Hollywood film techniques crept into other genres. Military adventure films, mixing action with patriotic ideology, had long followed the Soviet model of square, straightforward filmmaking. But by the 1960s the expressive noir light and shadow of Hollywood could be found in films like Living Forever in Burning Flames (1965, dir. Shui Hua), spotlighting the individual suffering and emotional drama of revolutionary martyrs. There was also a greater sense of exoticism, as many films, such as Mysterious Traveling Companion (1955, dirs. Lin Nong and Zhu Wenshun) and Visitors on the Icy Mountains (dir. Zhao Shinshui, 1963) were set along the Chinese border regions. These locales provided a sense of escapism to the masses. They also dealt with issues of national identity, examining the relationships between the Han Chinese soldiers guarding the frontier and the ethnic minorities native to these territories, with loyalty and trust on the line. In this sense, they were China's equivalent of Hollywood westerns.

Perhaps the most unique Chinese genre was one that didn't feature Han Chinese at all. Ethnic-minority musicals were wildly popular, a sensory feast of music, dance, and romance. Romantic love was still considered a bourgeois concept, so Han Chinese were largely forbidden to express it onscreen. But ethnic minorities, with their exotic, non-Chinese features, were excluded from this restriction. In Five Golden Flowers (1959, dir. Wang Jiayi), a Bai minority youth searches for a maiden named Golden Flower that he had met but once. In his search, he mistakes four other women, also named “Golden Flower,” before he finds the right one. One “Golden Flower” works at a foundry, another drives a tractor, one is a stockyard worker, and one is "an exemplary manure collector." Far from being merely a comic farce, this setup enables the government to highlight the active roles performed by women in work communes during the Great Leap Forward.

The roles of women characters in cinema during this period were indeed expanding, and yet their emotional life was still restricted. In contrast to the romantic openness of ethnic minorities, Han Chinese on the screen often had to sublimate sexual desire for revolutionary desire. Female characters often showed the most revolutionary passion. In Li Shuangshuang (1962, dir. Lu Ren), the title character is a village wife who is in a Maoist fervor to have her village meet model standards. She exposes the lazy, selfish, and reactionary elements among her neighbors, friends and family, including her own husband. Li Shuangshuang's uncompromising stance toward her community foretold the kind of behavior that would explode full-scale during the sweeping, destructive purification campaigns of the Cultural Revolution just a few years later.

One director who made women his major theme was Xie Jin, who above all could be considered the first auteur of Communist Chinese cinema. Xie vigorously explored the revolutionary potential of women, both thematically and cinematically, while moving effortlessly across genres. In Woman Basketball Player No. 5 (1957), Xie utilizes sports filmmaking to demonstrate an invigorating modern vision of female bodies in motion, displaying more flesh than had ever been seen in a Chinese film. In The Red Detachment of Women (1961), Xie positioned women firmly in the violent revolutionary struggle. It was a film so popular that it became adapted into one of the few plays allowed during the Cultural Revolution. In both of these films, Xie's women are vital, dynamic, and expressive. But it was with his next film that he—and the Chinese Communist cinema—achieved an apotheosis.

Two Stage Sisters (1965) is an epic saga involving two young women opera performers whose evolving relationship parallels the evolution of the Chinese Republic. Like so many films of this era, Two Stage Sisters is a national origin story, but more than any of the others, it puts forward the theme of history as a drama to be played. One sister adopts bourgeois capitalism like a stage costume, while the other discovers Marxist humanism through May 4th art and literature—in one shot, she literally wears it like a mask. One ideology proves to be all style, the other substance.

Two Stage Sisters feels like a culmination of the contradictory forces that shaped Communist Chinese cinema up to that point. It combines May 4th-style social critique with Maoist optimism. Its narrative chorus pays homage to traditional Chinese folk opera while suggesting the modern distancing devices of Bertolt Brecht. It infuses Marxist liberation theory into a classic women's melodrama straight out of Hollywood. Above all, Two Stage Sisters is a story of how art itself is a means for both societal reconciliation and revolution. One sister is seduced by a bourgeois businessman, while the other retaliates against the injustices around her. The system eventually stages them against each other in a corrupt court case, but the sisters literally break from the script, causing a revolutionary overthrow of the oppressive order.

Two Stage Sisters was finished at the eve of the Cultural Revolution. During this time, Mao Zedong’s wife Jiang Qing, herself a former movie actress, declared films to be “poisonous weeds” that threatened to subvert the goals of the Revolution. Two Stage Sisters was never even released; it was banned for promoting “class compromise and bourgeois humanism.” Eventually, all but a few movies were banned, and most production halted nationwide. Filmmakers were sent to labor camps. Seventeen years of filmmaking progress was shuttered. It would be decades before China regained what it had accomplished in developing its own cinema. Today, 60 years after the founding of the People’s Republic, films from China, such as Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002) and Jia Zhangke’s The World (2004), are still shouldering the immense, high-stakes responsibility of projecting their nation onscreen. In doing so they continue the legacy of the first films of the People’s Republic. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

A Revolution on Screen, Pt 2

A Revolution on Screen, Pt 2

Revolution on Screen Part 2

Revolution on Screen Part 2

RELATED CALENDAR ENTRY

September 26–October 6, 2009 (Re)Inventing China: A New Cinema for a New Society, 1949–1966KEYWORDS

video essay | Xie Jin | Chinese cinema | Cold War | Mao Zedong | social classes | Hollywood | genre | propagandaRELATED ARTICLE

A Revolution on Screen, Pt 1 by Kevin B. LeeThe People's Director by Leo Goldsmith

More: Article Archive

THE AUTHOR

Kevin B. Lee is editor of the Keyframe journal at Fandor and programming executive at dGenerate Films.

More articles by Kevin B. Lee