A Revolution on Screen, Pt 1

"A Revolution on Screen" is a two-part video essay coinciding with the 2009 New York Film Festival Masterworks series "(Re)Inventing China: A New Cinema for a New Society, 1949–1966." This series is the first major U.S. retrospective of the films made during the "Seventeen Years" period between the establishment of the People's Republic of China and the Cultural Revolution. Part 2 will be published next week.

On October 1, 1949, the People's Republic of China was founded. The ruling Communist Party, led by Chairman Mao Zedong, set forth on a mission to create a new nation, liberated from Western and Japanese imperialism as well as ancient feudal culture. The People's Republic would assert China's independence, not just politically and economically but culturally. The founding of a national cinema, one that was boldly and uniquely Chinese, was critical to this mission.

From the beginning, Party leaders understood the power of movies to captivate the masses and sway them to adopt their ambitious social programs. The challenge was to devise a cinema that would convey these messages effectively across the nation. By 1949, only a tiny fraction of Chinese had even seen a movie, as theaters were mostly in the big cities. Cinema had existed in China since the start of the century, especially in the cosmopolitan city of Shanghai, but the new regime rejected almost all pre-existing films as bourgeois. The new cinema of the People’s Republic had to be simple in concept and straightforward in execution to appeal to as many people as possible.

To develop this new artform for the masses, Mao’s cultural architects looked to one of China’s most revered artistic traditions, the opera. Chinese opera, with its clear character types, iconic expressions, and overpowering music, provided a blueprint for a people’s cinema, one where the camera, like an opera performer, moves through the moment, until it freezes in a powerful gesture. Filmmakers also embraced the Soviet model of socialist-realist cinema. These films conveyed positive portrayals of the working masses, promoting collectivism and mass mobilization, with less emphasis on the individual, the psychological, and the emotional, traits common to Hollywood films that the Party considered decadent.

Bridge (1949, dir. Wang Bin), the first feature film made in the People's Republic, establishes many of these elements. Nearly 10 minutes pass before a single character is addressed by name; mostly they call each other “comrade.” It feels like a bold new vision of collectivist cinema, but eventually it settles into a traditional character-driven narrative about the construction of a strategically vital bridge during the war against the Nationalist army. The film introduces character types that would become mainstays of PRC cinema for years to come. On the one hand, there's the smug, Westernized bourgeois; here he’s an engineer who doubts that the bridge can be completed with existing resources. He's matched against a heroic laborer who combines his ground-level expertise and proletarian charisma to rally his comrades to the cause. The ending is a foregone conclusion; the only suspense is in whether the bourgeois engineer joins the struggle. In this case, he is successfully reformed; in subsequent films, his kind usually wasn't so lucky.

Bridge is a cornerstone for the filmmaking that prevailed through the ’50s: simple, clear exaltations of workers, peasants, and soldiers. But there was also an undercurrent of films influenced by the May 4th Movement, a school of leftist critique that predated the revolution. These films were less propagandistic and more focused on burrowing deeply into the social mechanisms of oppression that plagued China for generations. Many of them were adaptations of May 4th literature, and yet they featured some of the strongest cinematic work of that time.

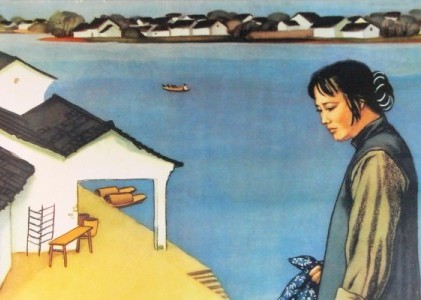

New Year Sacrifice (1956, dir. Sang Hu) is the story of a widow's exploitation at the hands of a brutal patriarchy, adapted from the work of famous May 4th writer Lu Xun. Whereas the source novel uses the nuanced, detached perspective of a bourgeois narrator, the movie achieves a direct, first-person portrayal of underclass suffering. This is done largely through a Chinese opera technique underscoring strength and clarity of image and feeling. The musical soundtrack reinforces the link to Chinese opera, intensifying dramatic and emotional states. Given that the film is about a woman who has no voice in her own fate, the expressiveness of the music, often used in place of dialogue, is especially heartrending. While the widow is given the standard iconic treatment, she’s ultimately a tragic figure, a dramatic break from the Communist heroes that dominated the screen. The filmmakers had to add an epilogue to assure audiences that her pre-Revolutionary fate would never happen in the present day.

Family (1956, dirs. Chen Xihe and Ye Ming) tells a story of young members of an aristocratic household buckling under the weight of an unyielding patriarch. In evoking a slowly dying way of life, it approaches the devastation of Orson Welles's The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). Its slow, creeping camerawork scours its feudal setting, probing the oppressive qualities of Confucian family spaces. Made in an age of collectivist culture, its sensitivity to individual emotional states feels stolen from another world.

While these May 4th-inspired films shared the same progressive sentiments, they also bore a dark, antiestablishment streak that made them dangerous to the ruling powers. This Life of Mine (1950, dir. Shi Hui) tells the story of an honest, humble Beijing policeman whose unwavering trust in the ruling authorities does nothing to stop the oppression of his family. But a critique of the old regimes could be misconstrued as a critique of the new one. Films like This Life of Mine had to find a balance between carrying the May 4th critical legacy and functioning as simple, Maoist propaganda. Even Shi Hui, the director and star of This Life of Mine, couldn’t manage this balancing act. Just a few years later, Shi was accused of being a bourgeois sentimentalist who valued artists over the masses. Faced with overwhelming criticism, one of the brightest talents of Chinese cinema drowned himself.

These outstanding films were the exceptions that proved the rule that in the age of mass culture, artists seeking complexity had to be self-effacing. Any desire for nuance or subtext had to be smuggled into the generic messages imposed by the Party. But as Chinese cinema continued to evolve, the template itself would be subject to revision, leading to a blossoming of forms that was as full of splendor as it was short-lived. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

A Revolution on Screen, Pt 1

A Revolution on Screen, Pt 1

Revolution on Screen Part 1

Revolution on Screen Part 1

RELATED CALENDAR ENTRY

September 26–October 6, 2009 (Re)Inventing China: A New Cinema for a New Society, 1949–1966RELATED ARTICLE

The People's Director by Leo GoldsmithA Revolution on Screen, Pt 2 by Kevin B. Lee

More: Article Archive

THE AUTHOR

Kevin B. Lee is editor of the Keyframe journal at Fandor and programming executive at dGenerate Films.

More articles by Kevin B. Lee