The Intimate Gaze

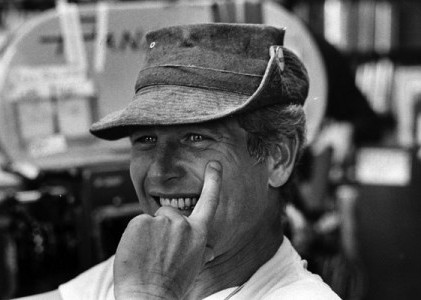

Much has been written about the late Paul Newman’s blue eyes. But it's strange that his way of looking at people and things through the camera aroused so little interest during his lifetime. Newman directed officially six features from 1968 to 1987 (I suspect he also had a hand in James Goldstone's Winning and Stuart Rosenberg's WUSA), which implies that he stayed inactive behind the camera for the last 21 years of his life. I have no way of knowing—did anyone interview him about this side of his work?—whether Newman felt frustrated, if he ever had any project he could not get financed or simply got disillusioned at the utter lack of attention (not to mention recognition) that met his work as director. I’m under the impression that his efforts were treated rather as a star’s whim, all his films being too modest and quiet—almost like Jacques Tourneur’s—to risk being accused of megalomania or even ambition.

Low-key, austere, episodic, halting, slow: These were some of the (rather damning) descriptions his films drew from critics. At best, they were called delicate, sensitive, or sensible, ancient but old-fashioned virtues for the late ’60s, and even more so after. His style was considered "unobtrusive" (bless him), visually undistinguished, plain, tentative, hesitant, or standard—in particular when he made The Shadow Box for TV in 1980. All his films were adaptations of novels or plays, save for the original (co-written and co-produced with R.L. Buck) Harry & Son (1984), reputedly his most “personal” film (and certainly not his best although still very good). That he took over from Richard A. Colla, as star and producer of Sometimes a Great Notion (aka Never Give an Inch, 1971) did not help that most interesting film’s reputation, already at risk because it dealt with a redneck family, which was neither politically correct nor cool. Besides looking rather like a Ken Kesey update of Delmer Daves’s Spencer’s Mountain (1963), which is, after all, in the great but not very popular tradition of John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley (1941), this was the only one of Newman’s films as director without his longtime wife, Joanne Woodward, in the cast. These two were also the only films Newman directed in which he also acted.

Eschewing sentimentality, histrionics, and dramatic tours de force, Newman’s films were always quiet and serene, no matter how terrible or sad the events depicted or implied. Most of his characters were neither happy nor rich, but they never whimpered or gave speeches to the audience. Newman looked at them level-headedly and with understanding, sometimes with concealed compassion; the actors were directed with the most precise flexibility. Even newcomers or otherwise difficult or hammy old ones were magnificent under his guidance (Christopher Plummer in The Shadow Box had his best role since Nicholas Ray’s Wind Across the Everglades and forgot all his mannerisms—unless they were "in character"). They seemed not to perform, but merely to exist before the camera, which was always placed at the right distance, keeping track of their most intimate feelings as conveyed or unwillingly revealed through their eyes, movements, silences, pauses, or gestures, never stressed or underlined by a cut or a tracking shot.

As a director, Newman depicted characters he cared for. He was fair enough to them not to hide their limitations or faults. He did not give them false, conventional happy endings. They had no one to deceive or cheat: it was an affair strictly between Newman and his characters, regardless of the audience, which was not their concern. Newman as director tried to understand them and let the audience watch, without encouraging any sort of artificial identification. He never flinched in front of risky, difficult scenes, of the sort most filmmakers elude with a sudden fade out or a jump cut. He went straight to the point, to where it hurts, and stared hard and long, unafraid of ridicule.

I see Newman the filmmaker as a sort of unconscious missing link between the "lost" (or "injured") generation of Nicholas Ray, Elia Kazan, Richard Brooks, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, Robert Aldrich, John Huston, Otto Preminger, Vincente Minnelli, Joseph Losey, Jules Dassin, Robert Rossen, Abraham Polonsky, and Orson Welles, and a more "modern," less plot-driven American cinema whose few truly daring representatives, from John Cassavetes, Shirley Clarke, or Kent Mackenzie to Michael Cimino, Abel Ferrara, or Charles Burnett usually did not last in full or free activity very long. (That the other great one was also an actor—John Cassavetes, of course—must mean something.)

Newman’s first directorial effort, Rachel, Rachel (1968), a penetrating and balanced portrait of a lonely small-town schoolteacher getting dangerously past her prime and belatedly discovering love and sex, should have encouraged his transition from acting to filmmaking along the lines that Clint Eastwood was soon to follow successfully. But Rachel was neither spectacular nor cute, refusing both soapbox opera and frustrated-spinster-demagoguery. Perhaps it felt like an old-fashioned, stagy, William Inge-ish piece in the revolutionistic culture of the period. Yet it already made me recall André Bazin’s insightful article about the cinematic challenge of filming a stage play whole, without “airing” it artificially. Newman managed to concentrate on characters and carefully avoid melodrama, two of his distinctive attributes as a director.

Not planned or designed by Newman, Sometimes a Great Notion (1971) is perhaps his most uneven work, partially salvaged at the last moment. But his way of looking at the characters and of confronting a difficult scene made it occasionally very moving and truthful, and almost casually, unintentionally beautiful. And I’m quite sure he enjoyed directing the likes of Henry Fonda, Lee Remick, and Richard Jaeckel, all members of a large, conflicted three-generation family (including in-laws) of Oregon loggers. More sprawling than every other Newman film, it shows he could have succeeded as well in the epic mode.

Then came Newman’s most ambitious project, a second gift to his talented actress wife. Adapted by Alvin Sargent (one of the best screenwriters of the period) from a play by Pulitzer Prize winner Paul Zindel, the electrifying The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-Moon Marigolds (1972) uses the camera as a sort of microscope to get inside the characters by staying respectfully outside and looking very intently on them. Reaching something quite uncommon, which I would call the nakedness of truth, it is a very simple film, so hard-edged it hurts, fully and intimately centered on a woman and her troubled daughters.

Still more impressive in its absolute modesty and to-the-point exploration of life’s last sparks is his next film, The Shadow Box (1980), largely unseen and often dismissed for being a TV movie. This is probably the deepest and most serenely harrowing film I have seen about illness and death, about loneliness despite love and the strange, complex relationships one weaves with relatives and close friends. Newman was treading the most dangerous ground, with the fearsome subject of terminal illness and agony. Bathos, sentimentality, cheap melodramatics, and tearful explosions hover over that kind of film, ready to cripple it at the slightest distraction of its makers. That he wholly and without visible effort avoided all these traps proves Newman’s achieved mastery as a filmmaker (he knew what he wanted to keep out, as well as what he wanted to get) and his maturity as a human being. Cassavetes could be more passionate, rough-edged, and brutal, and his movies were full of energy, but Newman had an edge in precision and balance, and the ability to mix the most concrete, realistic behavior and the most abstract settings.

Most people read Harry & Son as a metaphoric transposition of the feelings and reflections of Newman after the death of his own son Scott. Probably that notion has projected over the film a sort of sentimentality that he, both as actor and as author-director, was trying to keep at bay. I think he succeeded, but it’s useless—all but the most innocent or uninformed of viewers is contaminated by that knowledge.

And then came his unintended last work, The Glass Menagerie (1987), which one must not take as any sort of testament, but as probably the best screen version (together with a couple of shorts made in Germany in the late ’70s by the ailing Douglas Sirk) of a Tennessee Williams play, the one that finally caught the poetry and longing and fantasy (not only the sound and the fury) of this playwright’s creatures, almost mad with desire and loneliness.

It is, certainly, a small body of work but one of the highest quality and elegance. Newman needed not to become famous or rich, being both already. His was a labor of love—to films, to drama, to actors, to writing, to life. Also to his country, I think, because all of them could be classified as Americana, which is probably one of the reasons for his neglect as director. And very specifically, I’d say, a token of love to his own Anna Karina, his Marlene Dietrich, his Ingrid Bergman, his Lillian Gish: Joanne Woodward, who was never better than in those five of these six films in which she appears. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

The Intimate Gaze

The Intimate Gaze

THE AUTHOR

Miguel Marias is an economist who has written on film since 1966. The director of the Spanish Film Archive from 1986 to 1988, he is the author of books on Manuel Mur Oti and Leo McCarey.

More articles by Miguel Marias