Unreliable Narratives

If Born on the Fourth of July was Oliver Stone's retaliation against the mythography that governs the minds of Americans, JFK was an all-out offensive to reclaim the truth of one of America's most tragic events, the shooting of President John Kennedy. Asserting that the assassination of JFK was nothing less than a government conspiracy, JFK mixes archival footage with documentary-style reenactments, infusing commonly accepted facts with first-person speculation.

JFK disassembles the authority of the Warren Commission, tearing a series of holes in the commission's report through a sustained barrage of questions amplified by a disruptive visual rhythm. To quote the director, "I believe the Warren Commission Report is a great myth. And in order to fight a myth, maybe you have to create another one, a counter-myth." But what does Stone mean by "counter-myth?" Is JFK a "counter-myth" whose aim is to destroy the mythmaking apparatus altogether? Or is it to replace the old myth with a new one?

From the opening newsreel Stone presents a myth, one that pervades this stage of his career: government as oppressive patriarch, motivated largely by military and capitalistic interests and operating largely out of view of a public blinkered by patriotic propaganda. This government, Stone asserts, treats its subjects like children. But JFK goes further to reach a darker conclusion concerning the effects of a nation denied access to reality. When the government hides the true story and treats its citizenry like children, the children are bound to make up their own stories.

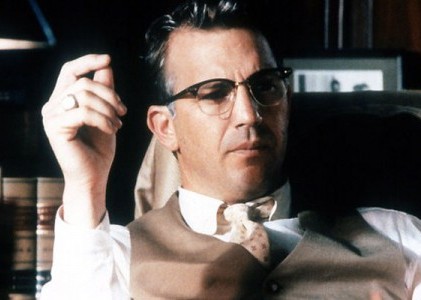

Remarkably, Stone rests the narrative argument of JFK upon the stories of two such children: David Ferrie and Willie O'Keefe, whose off-the-record testimonies implicate Clay Shaw, the only man brought to trial for conspiracy to kill Kennedy. O'Keefe is a fictionalized composite of several gay hustlers and felons loosely acquainted with Shaw. And yet his narrative takes center stage during a key point of the film, the interrogation scene between Garrison and Shaw. Shaw's polite demurrals to Garrison's questioning are repeatedly interrupted by cutaways to a contrary depiction of his involvement with O'Keefe, undermining Shaw's authority. The subjectivity of O'Keefe's account is never questioned, all but convicting Shaw in the viewer's eyes. Ferrie, a suspected key player in the assassination of JFK, is portrayed as emotionally disturbed and prone to lying. And yet, in a crucial scene that amounts to a validation of Garrison's case, Ferrie lays bare his involvement in a grand conspiracy to kill JFK.

Why does Stone give the accounts of these seemingly unreliable characters, people whom in the light of day you wouldn't want to shake hands with, let alone trust their stories, such a disproportionate amount of regard? In a perverse way, it reinforces Stone's main argument: if you fundamentally mistrust the grand narrative that has been imposed on the general populace, where else to turn but to the discredited, the outcasts, those left by the wayside of the ruthless march of history as dictated by the ruling powers?

One might say that Stone's cinema in JFK turns its viewer into such an outcast. This fusillade of imagery tears a hole in the fabric of truth, bombarding the viewer with the perpetual sensation of forbidden revelation. We are forever divorced from a pure, unquestioning acceptance of history as given to us by the mainstream. What we are left with is the impression of reality as a grim, deterministic struggle between various forces competing to wield the most compelling, most seductive narrative for us to accept.

In the middle of this is Stone's cinema, carrying the viewer aloft in its sheer force, disorienting in its persuasiveness, persuasive in its disorientation. Not unlike the authoritarian forces against which Oliver Stone wages movie warfare, instead of speaking truth to power, JFK speaks cinematic power to truth. — K.B.L. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

KEYWORDS

video essay | Oliver Stone | Hollywood | Cold War | patriotism | American President | film review | biopicRELATED ARTICLE

Arsenic and Apple Pie by Kevin B. Lee and Matt Zoller SeitzFear and Self-Loathing by Kevin B. Lee and Matt Zoller Seitz

Empire of the Son by Kevin B. Lee and Matt Zoller Seitz

Follow the Leader by Kevin B. Lee and Matt Zoller Seitz

More: Article Archive

THE AUTHORS

Kevin B. Lee is editor of the Keyframe journal at Fandor and programming executive at dGenerate Films.

More articles by Kevin B. LeeMatt Zoller Seitz is a writer and filmmaker whose debut feature, the romantic comedy Home, is available through Netflix and Amazon. His writing on film and television has appeared in The New York Times, New York Press, and The Star Ledger, among other places. He is also the founder of The House Next Door, a movie and TV criticism website.

More articles by Matt Zoller SeitzAuthor's Website: The House Next Door