The Dream Life

What appeals to me most [about Surrealism] is an idea expressed by Eluard. He has a line about there being another world, but it’s in this one.

—Edward Gorey, interview (1978)

The Vampires’ labyrinthian conspiracies imbue Feuillade’s near-documentary presentation of 1915 Paris with an awesome sense of unreality, presaging poet Paul Éluard’s dictum “There is another world, but it is in this one.”

—J. Hoberman, review of Louis Feuillade’s Les Vampires (1983)

Edward Gorey (1925–2000), the supremely eccentric illustrator and author, said that he used to watch a thousand movies a year. Gorey came to New York in 1953, where he attended the exclusive cinephile screenings of Ted Huff and then William Everson, who would become head of NYU’s cinema studies program. (The latter’s circle of viewers included everyone from Lillian Gish to Martin Scorsese to various New Yorker writers to Susan Sontag to Mel Tormé.) Later, Gorey would review movies for the Soho Weekly, under the anagrammatic pseudonym “Wardore Edgy.”

Gorey also claimed to have exhausted the film archives at the Museum of Modern Art. There he immersed himself in the multipart crime epics of Louis Feuillade (not just the famous Fantômas and Les Vampires but the all-but-unseeable Tih Minh and Barrabas, “the greatest movie ever made”) and encountered one of his “great influences,” “a film that no one ever put together”:

The Museum of Modern Art just had all the footage of it. It was Italian, it was a serial, it was called Grey Rats. But it was completely out of context. You’d be watching and say, “Oh yes, that happened half-an-hour ago.” Somebody had thrown it all together in a big box, on reels, and we watched it that way, it took about two weeks.

This is the dream life: obsessive eyeball mileage, movies as long as a night’s sleep, scenes shuffled out of order, cause following effect, sustained silences in which mouths move and every title card seems to crystallize the swarming drama into koans.

Even a casual admirer of Gorey’s work—with its heightened poses and penumbral malevolence, deft text and impeccable texture—can detect that quality of oneiric distillation it shares with silent film. This affinity makes the handsome recent publication of The Black Doll (Pomegranate, 71 pp., $17.95), Gorey’s “silent screenplay,” not so much a revelation but the happy, one-time offshoot of a fully formed aesthetic sensibility.

The screenplay dates from 1973; it was originally published 11 years ago in Scenario magazine, along with an illuminating interview with Annie Nocenti (included here). A sort of fantasy Netflix queue can be assembled from the films Gorey mentions to Nocenti: Chaplin’s swansong, The Countess From Hong Kong; “endless numbers of D.W. Griffith two-reelers”; The Lady Vanishes (“my favorite thriller of all time”); The Perils of Pauline; Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (“my favorite horror movie”) and Judex (“one of my favorite movies”); Jacques Tourneur’s The Curse of the Demon (“a marvelous low-budget movie”); Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire and The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz; Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Diabolique (“one of the truly great films”) and La Prisonnière (“one of the great goofy movies ever made”); and much more.

Most of these are films he’s obsessed with, to some degree, as can be seen by his generosity with superlatives. (It should be noted that some things—Flaubert’s Salammbo, and especially Body Heat—do drive him batty.) But this bubbly, astonishingly well-informed cinephile also mentions some films that he’s never had the chance to see, possible dreams he can never inhabit: Feuillade’s The Two Orphans (“part thriller and part domestic drama”) and his original Judex. Most haunting of all might be a film Gorey made himself, one that, ironically, he could only glimpse: “a half-hour film that got lost after the rough cut was made.”

***

The Black Doll itself is an unseeable film, though invisible, in this case, for having never been made. Gorey lists a few directors he could dream helming a production: Werner Herzog, Lars von Trier, Pedro Almodóvar, Francis Girod (The Infernal Trio, “one of the great dippy movies ever made”), Jean-Pierre Mocky, and Stephan Elliott, of The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert fame. (The perfect director for The Black Doll, of course, might be the title-card-carrying Guy Maddin.)

In his books, Gorey’s words are as distinctive as his drawings; his unerring sense of proportion welds the two in the reader’s mind. (Gorey’s first book, The Unstrung Harp, a formidably hilarious account of authorial angst, consists of 30 paragraphs matched with 30 drawings; it expands in the memory to novel-like proportions.) Though this book-sized edition of The Black Doll contains marginal illustrations, they bear no direct relation to the manuscript. Fortunately, Gorey’s prose has a rewarding lightness of its own, and his encyclopedic knowledge of silent-film conventions makes The Black Doll an enjoyable read in its own right. The images aren’t there, but his words conjure them vividly.

The prologue, “What Went Before,” is two parts plot propellant to one part vintage Gorey whimsy. “A thousand years ago there flourished in central Asia a city called Gulb (or Blug),” it begins. “It was rich and powerful, and its inhabitants worshipped the Bear That Dances.” It is 1910; an expedition to the ruins of Gulb/Blug uncovers a priceless ritual object (the “PRO”), which stimulates “various interested and opposing parties” into action. (The PRO, deliciously, is never glimpsed, nor is its appearance described.) No fewer than five factions engage in spying and subterfuge to attain the object, not counting the daughter and would-be son-in-law of the PRO’s discoverer, Professor Bedsock. How all of this information would be delivered to the hypothetical viewer is unclear, perhaps irrelevant.

Bedsock sends the PRO to his daughter after embedding it in the Black Doll, a limbless, faceless effigy identical in appearance to a seemingly limitless number of circulating black dolls. What follows is a whirlwind of activity in which black dolls are swiped, replaced, eviscerated, and abandoned, in a mounting frenzy of futility. (In his foreword, Andreas L. Brown notes The Black Doll’s MacGuffin motif, seeing possible links to its use in The Night of the Hunter, Wait Until Dark, and The Maltese Falcon.)

The scenario is a throwback—the smallest part parody perhaps, even a touch camp. But the mechanics are pleasingly sound, and every page reveals Gorey’s attention to detail and all manner of inspired touches. Just as the black dolls are indistinguishable from the Black Doll concealing the PRO, many of the minor roles (Joshua the servant, assorted thugs and “Asiatics”—the latter requiring taped eyes) are to be played by the same actor. “Though his appearance and clothes change for each character, there is never any doubt that it is the same actor; the only significance is that which meets the eye.”

That phrase resonates—a credo of sorts for someone who fastidiously avoided interpreting (at least publicly) what his uncanny work “meant.” (Part of his delight with the 1993 film Suture stems from the fact that nobody remarks that one identical twin is black, the other white.) Or else it’s a zen-ready conundrum: What if your eye imbues great significance to such repetitions and repackagings? To say that style is everything can be read as both deprecating and, slyly, elevating.

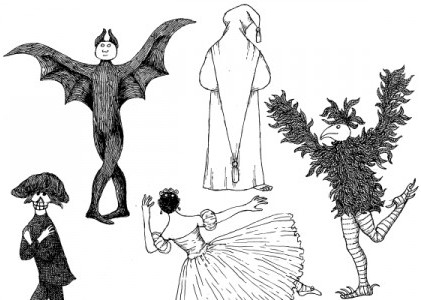

For there’s a purity to the (described) visuals on delirious display in The Black Doll, even as they disorient. The title sequence shows the ruins of Glub/Bulg as “an obvious, but not too, miniature constructed of clay, small stones, etc.”; the camera gradually moves forward, then suddenly pulls back, revealing the scene to be a photograph. A masked ball allows Gorey to revel in a catalog of costumes, beginning with “a lady in a white chiffon garden-party frock and a white organdy picture hat and skull mask, another in a white insect costume with transparent wings and a mask with antennae, etc., and a man inside a black obelisk, trompe l’oeil stones painted on canvas, with a shiny white oval mask.” (An obelisk?)

In the first of the film’s eight sequences, Daisy, the professor’s daughter, picks up the phone:

Closeup. In the abandoned mill, hands wearing pallbearers’ gloves hold a telephone.

Title. (Daisy) “Hello…hello…is anyone there?”

One of the hands turns on a phonograph, puts the needle on a record, and then holds the mouthpiece of the telephone inside the horn of the phonograph. Daisy, in bewilderment and horror, listens, and then thrusts the phone from her, and hangs up.

Title. (Daisy) “Oh, how dreadful!…a bestial orgy is going on somewhere.”

The unnatural (or all too natural?) mating of the telephone with the phonograph horn gives a premonition the orgiastic content of the record, which, perversely, we are not permitted to hear, this being a silent film. The hunch is confirmed by Daisy’s horrified outburst. But what kind of record would hold such noises? Gorey explains without explaining. Lurking in that gap between what’s understood and what can never truly be grasped is the secret power of his art. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

The Dream Life

The Dream Life

THE AUTHOR

Ed Park is the author of the novel Personal Days and a founding co-editor of The Believer. His nonfiction appears this year in Burn This Book (HarperStudio), Read Hard! (McSweeney’s), and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Exilée and Temps Morts: Selected Works (University of California).

More articles by Ed Park