Our Man in London

The Great Ziegfeld is another of those films which belongs to the history of publicity rather than to the history of the cinema. This huge inflated gas-blown object bobs into the critical view as irrelevantly as an airship advertising someone’s toothpaste over a South Coast resort. It lasts three hours: that is its only claim to special attention. Like a man sitting hour after hour on top of a pole, it does excite a kind of wonder; wonder at how it manages to go on....There is really no reason, except the patience of the public, why such a picture should ever stop.

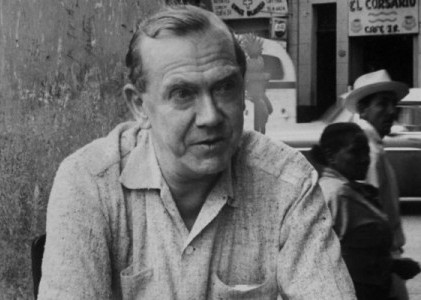

This is the chiming, level, altogether beguiling voice of Graham Greene, for a short while the best film critic writing in English, and it is a voice that comes across the transom these days with the clarity and strange intelligence of a Bach étude and thus has many things to say about film criticism as we’ve known it in the contemporary arena. By his own admission, in 1935 when Greene was a struggling novelist working on his sixth book, he accosted (at a party, “after the dangerous third Martini”) the editor of The Spectator and asked if he might review films for the paper. He thought it might merely be fun, and apparently it was—for almost five years, and as the nascent continental war spread from Poland to Scandinavia and the Baltic states, Greene rapped out compact, 750-word weekly dispatches for the paper and for the short-lived upscale magazine Night and Day, taking on three or four or sometimes five films in a pop.

Never out of print (now available in a miscellany from reprint house Applause Books) his collected reviews make for addictive reading, despite their culture-specific tics (the tiresomely polite addition of Mr. and Miss on to every surname, even going so far as to address German directors as Herr and so on). Greene was not a specialized, professional cinephile-reviewer (in the mid-’30s, who was?), but he was an aggressively cultured man and like James Agee after him was first and foremost a writer who wrote, and so his critiques struck a certain kind of public equipoise—all the expertise you needed to read him in the ’30s was that provided generally by public schools, and you certainly needed to read carefully. Yet how rashly different Greene’s discourse—nuanced and endlessly suggestive—is from film reviewing as we know it today, on either side of the Atlantic.

Of course, Greene’s relationship with cinema was complex; he was writing screenplays and selling novel rights even in the ’30s. (In a fascinating review of 1936’s One Rainy Afternoon, Greene affectionately slams Ida Lupino, saying she “is as yet a dummy, but she is one of the more agreeable screen dummies to whom things are made to happen, and I feel some remorse when I think of the shootings and strangulations she will have to endure next year in a story of my own.” She wasn’t eventually cast in 1937's The Green Cockatoo, but imagine a low-wage film critic today dishing an actress like that even as he has a script go into production.) Every reviewer has his or her distinct sensibility, but part of Greene’s charming battery of givens was a frankness about his prejudices—he was intensely skeptical about the new color processes (the 1935 landmark Becky Sharp scores points, but “the only complaint I have against Technicolor is that it plays havoc with the women’s faces; they all, young and old, have the same healthy, weather-beaten skin,” while in the 1936 British version of Faust, “the characters, with their faces out of focus, move with slow primeval gestures through a thick brown fog—the scarlet cap of Mephistopheles occasionally gleaming out of the obscurity with the effect of a traffic signal”).

He adored the pioneering documentary work of John Grierson and Basil Wright, took every opportunity to insult middle-range studio Denham Films (even when they produced, almost by accident, a decent movie), and often mocked the British censors by name (specifically, Mr. Benjamin Shortt, long forgotten but for Greene’s sly vituperations). He had a yen for Anna Neagle (tossing digs at 1935’s Peg of Old Drury, Greene rounds up, “But I am ungrateful: I have seen few things more attractive than Miss Neagle in breeches”), but took a cudgel to forgotten Brit ingenue Cicely Courtneidge, who “acts, acts all the time: it is as tiring to watch her as to watch the defeated boat-race crew strain raggedly after Cambridge up the Thames.” Greene held the utmost admiration and hope for Fritz Lang after Fury (1936) and came to appreciate Renoir only after La bête humaine (1938). As much as he always loved Harry Baur, he could not tolerate the moony Herbert Marshall, and a Marshall film would often unsheathe Greene’s most vivid similes, always canine in variety. In Girls’ Dormitory (1936), “Marshall, of course, has the damp muzzle of a healthy British dog,” and in If You Could Only Cook (1935), Marshall is seen as “something large, sentimental and moulting, something which confirms one's preference for cats.”

Prejudices, after all, are unavoidable; a critic can pretend he or she has none only via bald dishonesty and elaborate rationalization. What matters is a passion for the medium, and Greene had it in barrels. No genre defeated him, any incidental pleasure was worth the whole of a forgettable film, and he was responsive as few film writers have ever been to the raw force of human presence. While he recognized acting as a nebulous, soul-baring relationship with the camera lens (not, God forbid, Shakespearean chops, and the young Laurence Olivier gets lanced more than once), he also knew as Parker Tyler did that movie stars are 80 percent physical spectacle and voice. I could quote his acute, riotous perceptions all day, but let’s suffice with his evocation of Peter Lorre, whose “marbly pupils in the pasty spherical face are like the eye-pieces of a microscope through which you can see laid flat on the slide the entangled mind of a man: love and lust, nobility and perversity, hatred of itself and despair jumping out at you from the jelly.”

Regarding Carole Lombard, Greene maintains, "it is always a pleasure to watch those hollow Garbo features, those neurotic elbows and bewildered hands, and her voice has the same odd beauty a street musician discovers in old iron, scraping out heart-breaking and nostalgic melodies." Jean Harlow’s "technique was the gangster’s technique—she toted a breast like a man totes a gun," while Shirley Temple "acts and dances with immense vigour and assurance, but some of her popularity seems to rest on a coquetry quite as mature as Miss Colbert’s, and on an oddly precocious body as voluptuous in grey flannel trousers as Miss Dietrich’s."

In fact, Greene’s most famous review, of the John Ford-directed Temple vehicle Wee Willie Winkie (1937), became his Jude the Obscure, prompting 20th Century Fox and Temple’s lawyers to sue Greene and Night and Day for libel. Who knows who else was appalled, but for Hollywood this restatement of Greene's earlier opinions was just one film critic's toe too far over the line:

Infancy is her disguise, her appeal is more secret and more adult. Already two years ago she was a fancy little piece (real childhood, I think, went out after The Littlest Rebel). In Captain January she wore trousers with the mature suggestiveness of a Dietrich: her neat and well-developed rump twisted in the tap-dance: her eyes had a sidelong searching coquetry. Now in Wee Willie Winkie, wearing short kilts, she is completely totsy. Watch her swaggering stride across the Indian barrack-square: hear the gasp of excited expectation from her antique audience when the sergeant’s palm is raised: watch the way she measures a man with agile studio eyes, with dimpled depravity. Her admirers—middle-aged men and clergymen—respond to her dubious coquetry, to the sight of her well-shaped and desirable little body, packed with enormous vitality, only because the safety curtain of story and dialogue drops between their intelligence and their desire.

Scandalous, sure, but this also has the impact of all good criticism: it changes how you view the original. Watching Temple now is far from the snow-innocent family experience of yesteryear; Greene’s right, there’s something unsavory about the actress’s eye-rolling, hungry energy.

Greene was especially adept at blasting received clichés of history and culture, which in the Golden Age were wall to wall. (Of course, our retrospective view overlooks and even embraces the short cuts and lies of old studio product, which begs the question of whether cinephiles 50 years from now will find it easy to skim over the assumptions and bull in Pearl Harbor or Valkyrie or Frost/Nixon.) For Greene, the Paul Muni biopic Juarez (1939) was merely a bloated and facile trip through Mexican history, objectionable only (but notably) for eliding the Mexican president’s policy of anti-Catholic violence and church lands expropriation, the legacy of which Greene had gone to Mexico in 1938 to see for himself. (Hence The Power and the Glory.) Likewise, Greene observes the idealist climax of Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) as a "fairy-tale"; when Claude Rains’s corrupt politico, "like a Dickensian Scrooge, is caught by conscience, I imagine it is easier for us, than for an American who knows his country’s politics, to suspend disbelief."

From where he sat, 1935’s The Bride of Frankenstein could be lashed as “a pompous, badly acted film, full of absurd anachronisms,” and it’s difficult to argue that we might not have had the same reaction at the time, having grown up on Shelley and not Karloff. But because Greene was a narrative craftsman, you’d expect a practical approach to story, and there’s a special pleasure in seeing movies measured mercilessly by a great instinctual plotmaker. Even so, Greene’s measurement was most often brief and unassuming; plots could be recounted in detail if they were interesting (his breakdown of Jacques Feyder’s Knight Without Armor, from 1937, is more intriguing than the film), but usually he just agreeably, in a single sentence, allowed the films to be the modest, factory-churned ripoffs they were, without a spit of outrage.

In the ’30s, no film was a must-see “event,” blockbusters and tentpoles and “rollercoasters” had yet to be hatched from their golden eggs, and tickets still cost under 30 cents. So no release required epochal pronouncements and fatalistic declamations about the state of cinema, or make-or-break estimations about the viewer’s investment. Movies were just larks, to be consumed two at a time and two or three times a week, and movie critics like Greene could afford (even if they didn’t often enough) to regard the transaction with humor and easiness. (Greene’s use of the word “rather,” as in “rather dull” or “rather brisk,” speaks volumes.) He maintained an amused, objective air, with an effortless wit that The New Yorker’s Anthony Lane would sell his children for, but mostly he wrote—real sentences, with complex structures, unexplained allusions (to everything from 19th-century lit to cricket to contemporaneous politicians), breathtakingly presumed leaps in syntax, and descriptive language that makes your frontal cortex laugh out loud. Ironically, because Greene’s approach was never highbrow, modern film critics couldn’t write like this even if we wanted to and found ourselves able. Simply put, the readership, and/or the public schools that produced it, just isn’t up to it, on paper or online.

Greene being a preeminent novelist means as well that his semi-disposable reviews are preserved for posterity; as a result we come upon film after film that the organically evolving canon has long forgotten. He makes a soulful case for We From Kronstadt (1936), a Soviet epic of revolutionary chaos, and I’m on the lookout for it now, as I am for This Is My Affair (1937), in which Brian Donlevy, Robert Taylor, and Victor McLaglen play Edwardian, spat-wearing bank robbers. Likewise, he made a rare English-language pitch for Grigori Alexandrov’s 1934 farce Jolly Fellows (Jazz Comedy) and greets future partner Carol Reed with plaudits for his second and third films, neither of which are commonly available. Even his pans can make the films inviting. British reviewers apparently had to suffer a good deal of Austrian movies in the ’30s (enough for Greene to list an entertaining raft of singularly Austrian clichés), and they also had nascent Nazi culture to contend with, amid the post-Chamberlain appeasement phase—listen to Greene serenely, concisely pick the scabs off the Aryanized 1934 version of Joan of Arc, steering blame away from the lead actress:

For it is one of the purposes of this Nazi film to belittle a rival national saviour. The real hero is Charles [VII] with his Nazi mentality, his belief in the nobility of treachery for the sake of nations. The purge of June 30 and the liquidation of Trémouille, the burning Reichstag and the pyre in Rouen marketplace—these political parallels are heavily underlined. The direction is terribly sincere, conveying a kind of blond and shaven admiration for poor lonely dictators who have been forced to eliminate their allies. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Our Man in London

Our Man in London

KEYWORDS

Graham Greene | film criticism | book review | Shirley Temple | Hollywood | studio system | World War II | United KingdomTHE AUTHOR

Michael Atkinson is the author/editor of six books, including Ghosts in the Machine: Speculating on the Dark Heart of Pop Cinema (Limelight Eds., 2000), Flickipedia (Chicago Review Press, 2007), Exile Cinema: Filmmakers at Work Beyond Hollywood (SUNY Press, 2008), and the novels from St. Martin's Press Hemingway Deadlights and Hemingway Cutthroat.

More articles by Michael AtkinsonAuthor's Website: Zero for Conduct