Of Ghosts and Phantoms

The following texts on Manuel Mozos were published in the program of the 2012 Viennale on the occasion of a Mozos retrospective, presented by Miguel Gomes, and are reprinted with permission of the Viennale and the author. The text on Xavier was translated from the German by Kurt Beals.

I first met Manuel Mozos in February 1999, at the Fantasporto Fantastic Film Festival in the northern Portuguese city of Porto. Manuel was there to attend the first public screening of his film, ... quando troveja (When It Thunders), and I was writing up the festival as a film critic for a daily paper. The film left me deeply impressed, and I managed to get an interview with Manuel, one of the few interviews during my brief stint in journalism.

Our next encounter was two years later, when I was writing a book on his films for the first Manuel Mozos retrospective at the Festival de Cinema Luso-Brasileiro in Santa Maria da Feira. In the two intervening years, we had forged closer ties: I had asked him to edit my short film, Inventário de Natal (Christmas Inventory, 2000), and his work had given me the courage to take a stab at editing my films myself.

...quando troveja was never far from my mind and when I started on my first feature film, The Face You Deserve, I wanted it to enter into a dialogue with Manuel's film. And as it is, in both works fantasy characters turn up in the midst of the protagonists' life crisis. In Manuel's film, these are two spirits of the woods; in mine it is a direct reference to the story of Snow White. I asked Manuel to co-write the script with me and he took on the role of a dwarf, Harry, an even-tempered conniver.

Um passo, outro passo e depois

As I see it, Manuel is the one great Portuguese filmmaker who has been denied the international acclaim he is due; but I am not alone in feeling strongly for him and his films. The two key figures of 1960s filmmaking and pioneers of modern Portuguese cinema are closely linked to his work: Fernando Lopes (Belarmino, 1963) asked him to make his first, hour-long film for Portuguese television, Um passo, outro passo e depois (A Step, Another Step, and Then). And the late Paulo Rocha (Os Verdes Anos, 1962) took on the production and finishing costs for Manuel's second film, Xavier, which, for lack of money, awaited completion for many years.

Xavier was shot in 1991 but not completed until 2002—a time during which Pedro Costa and Teresa Villaverde, who are now far better-known internationally, began making films, as did a number of other Portuguese directors who have since disappeared without a trace (Joaquim Pinto, Victor Gonçalves, Daniel Del-Negro, Ana Luísa Guimarães, ...). Of this phantom generation, Mozos was the most prolific. This is because even though Xavier was not released for many years, a fact that was to profoundly affect his further career, Manuel still continued to work in the area of documentary filmmaking.

In 1994, with Lisboa no Cinema, he embarked on a series of films on Portuguese cinema, for which—in a wonderfully subversive maneuver—he appropriated the images and cinema of others in order to allow him to go on making his films. His obsessive as much as unique rapport with Portuguese cinema can be seen in the extraordinary documentary Cinema Português (...)?. In 2008, Mozos returned to feature films with 4 Copas, a project that is generally regarded as less ambitious and less personal than his earlier works but in which we still recognize the dignity and the frustration of the characters that the director has introduced us to. In the context of contemporary Portuguese cinema, these characters seem almost anachronistic—and all the more beautiful for it.

After that, Manuel largely focused on documentaries (not entirely of his own volition as he failed to get funding for a feature entitled Ramiro). Among the montage films, artists' portraits—on a contemporary musician, a writer, and a fado singer—and films on national Portuguese cinema commissioned by the Portuguese Film Institute, for which he now works, one film stands out in particular: the brilliant and unique documentary, Ruínas (2009), an essay full of ghosts, about a country that cannot shed its memories.

Overall, we are talking about an oeuvre moulded by financial distress and thus one that tells us about the compulsion to fail: the failure of the country and of Portuguese cinema, the failure of Mozos's generation and that of Manuel Mozos the filmmaker. That such failure may constitute a chief contribution to contemporary Portuguese art and culture may seem paradoxical—except to those who get the chance to see Manuel's films. Because Manuel Mozos is a filmmaker who, for reasons of romanticism, will remain a phantom but one we cannot ignore. For if we do, the phantoms will be us.

****

The shooting of Xavier was interrupted in 1991, when it was just on the verge of completion—only two scenes were missing. The co-producer had gone bankrupt. Not until 12 years later, in 2003, could the feature-length film finally be completed in the form that we see today.

Xavier, one of the most subtle Portuguese feature films of the 1990s, exhibits the wide range of antitheses that characterize Mozos's work to this day. Like Nogueira in Um passo, outro passo e depois..., Xavier acts out of an almost existential sense of exclusion. It is a self-imposed exclusion, the sort strongly represented in Portuguese artistic production of the 20th century, particularly in literature, from Fernando Pessoa to Mário de Sá Carneiro. At first sight, it appears to have its roots in the opening scene, in which Xavier's mother (consummately played by Isabel Ruth) entrusts her young son to Catholic nuns in an orphanage. The only sign of the boy's father, who is never mentioned, is the lingering sense throughout the film that he is missing—a deep abyss of silence and absence, over which Mozos weaves a vast web of relationships between the characters.

Xavier

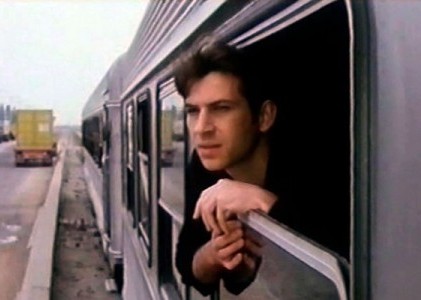

Xavier has much in common not only with Nogueira, but also with Nogueira's foil, Luís, in Um passo, outro passo e depois..., who, like Xavier, is powerfully portrayed by Pedro Hestnes. But whereas Nogueira lives out his excluded existence in semi-autistic exile, Xavier has a strong need to fit in, which leads him to constantly seek out new experiences and activities—always in motion, because there is no central point to which he can return. The film never seems to fixate on any specific location or any person but Xavier himself, who is condemned to a nomadic existence, both physically and affectively. Amid this constant coming and going, fleeing and rushing ahead, Xavier does not even realize when others have found their own place. This restlessness, the central theme of this remarkable film, may be more familiar in literature than in cinema. The search for one's own identity is reminiscent of Pirandello. Lacking a father, Xavier ceaselessly searches for other relationships to fill this void. Time and again, Xavier grows close but then pulls away, as father, son, brother—always in the desperate attempt to find his own place in the lives of others, as a member of their family.

We see Xavier return from the military to the house of Hipólito, a friend from the orphanage with whom he has formed a brotherly bond. We see how he hesitantly alienates his friend from Rosa, only to enter into his own tempestuous relationship, taking the place of his brother in suffering; how he goes back and forth between his godfather, Alves, and the nun Maria da Luz, as he attempts to free his mother from the mental asylum and place her in an old-age home. We see how he dreams of his godfather's daughter, his adoptive sister, who represents the opportunity for official integration into this replacement family.

If Um passo, outro passo e depois... can be described as a "filme de bairro," reflecting a familiar suburban world, the same can be said of Xavier. But this film, with its deep undercurrents and its complex web of emotions, takes on novelistic dimensions—yet another unusual aspect of contemporary Portuguese cinema. The melodramatic weight of loss has more in common with the Italian cinema of the 1960s (to some extent Antonioni, but above all Zurlini) than with the classical cinema of Douglas Sirk.

Xavier

Xavier, like Um passo, outro passo e depois..., is a film that weaves together the real and the everyday: chocolate factory, orphanage, old-age home, market, English lessons, cafés, the outskirts of Lisbon, train travel, new avenidas, gas stations, memories of the Portuguese colonial wars, dance performances with African music, Sunday picnics, and the appliance store.... But where these familiar sights of petit-bourgeois Lisbon intersect, an imaginary neo-romantic world emerges, discreetly overshadowed by orphanhood, insanity, and above all by the Catholic drive for penance, which causes Xavier to drift from realism into dreamlike and symbolic realms. But Xavier remains a "filme de bairro," and the characters encounter each other again and again, as if they inhabited a world of their own, even if this world is now Portugal as a whole, transformed into a purgatory in which disappointments and small pleasures bring people together around their painful scars.

There are no revolts; everyone accepts these losses with stoic resignation; they share the gentle melancholy of the fado songs that seem to emerge from the dramaturgical structure of Xavier (abortions, funerals, financial problems, aging, criminal trials, suicides, festivals, contests, smuggling, cigarettes smoked on the beach with the nun, or stamped out by the foot of an unknown person on the street corner, petty fraud in TV antenna repair...). With intelligence and a keen sense of self-irony, Mozos brings together this simmering chaos, all of these comic and tragic moments, to form a unified whole, but he gives meaning to each short segment, deftly crafting ellipses with a strong feeling for gestures and people, relationships and spaces.

Xavier is just as alone after these stations of the cross as he was at the beginning. His path inevitably leads him in a circle. After his mother dies, he goes to the country, then returns, finding Hipólito in prison. Rosa and Luísa are married, his godfather is old and has no say anymore in the chocolate factory, and Sister Maria returns home to die.

How can such a complex chain of events be captured on film? The magical cut at the end of the first scene freezes time and sets the stage for an eternal return, a fixed order in the cycle of places: Xavier's mother disappears at the gate of the orphanage that faces the train tracks, and a leap in time brings us to Xavier, filling the same portion of the frame, riding the train past the orphanage in which he had been left a year before. This is more than just an ellipsis; it is the cinematic inscription of the circularity of this film, the inscription of a movement that is always circular, that is only interrupted here and there to ensure that Xavier does not become rooted in place, that he does not become integrated into a group. It is the inscription of a movement in which space itself comes to a close—the space in which Xavier shuts himself up, incapable of opening it to escape from his isolation. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Of Ghosts and Phantoms

Of Ghosts and Phantoms

THE AUTHOR

Miguel Gomes is a Portuguese film director (Tabu, Our Beloved Month of August, The Face You Deserve).

More articles by Miguel Gomes