Morning in America

A Four-Pack of Carpenter, BAMcinématek, September 1-4, 2008

John Carpenter is the least pretentious American studio filmmaker of his generation. Like his more critically celebrated simpatico contemporaries—Brian De Palma, Joe Dante, and David Cronenberg—Carpenter has kept alive the mid-century B-movie tradition of using impersonal work-for-hire projects to fulfill an auteur’s vision. What's distinctive about Carpenter is how enthusiastically he embraces the hokiest conventions of the genres he works in. His films are cheeky, but not ironic. He has never, no matter the context, shied away from a gunfight or car chase. Indeed, Carpenter’s approach to zombies, psychopaths, aliens, and vampires is to take them all dead seriously as subjects.

Halloween (1978), the indie $400,000 ur-slasher classic that established Carpenter in Hollywood (and launched Jamie Lee Curtis’s stint as a virginal scream queen) was so coolly efficient in per capita goose bump production—it also grossed $47 million stateside—that even the disapproving Pauline Kael had to admit that “maybe when a horror film is stripped of everything but nightmarish dumb scariness and sudden shocks it satisfies part of the audience in a more basic, childish way than sophisticated horror pictures do.”

Her sneering aside, Kael’s “stripped” and “basic” are apt for Carpenter’s minimalist, unapologetically pop style. His movies almost always run between 90 and 100 minutes. They are heavy on atmosphere, but the spaces depicted are typically empty (Carpenter’s murky, underfurnished sets are the prototypes for Inland Empire’s interiors). Even the synthesizer scores, many of them written and performed by the director himself, are spartan. And yet for all their apparent simplicity and directness, the genre pictures Carpenter made during the 1980s are among the most radical readings we have of morning in America, as evidenced by BAMcinématek’s four-picture retrospective.

Escape From New York (1981), Carpenter’s fifth feature and the earliest in the series, takes place in a futuristic 1997, when the national crime rate has quadrupled, and Manhattan has been walled off and converted into a federal penal colony. Of course, the actual Big Apple of 1997, under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, was a place that seemed to be overrun by cops, if anything. But after a decade of Harry Callahans, Paul Kerseys, and Travis Bickles (what J. Hoberman has called the Legal Vigilante) failing to wash the scum off the streets, Escape From New York, for a lot of moviegoers, was death wish fulfillment, not science fiction.

Snake Plissken (Kurt Russell), however, isn’t an action hero in the 1970s mode. After rescuing the kidnapped president of the United States (Donald Pleasence, a Carpenter regular), Plissken unspools the tape of a speech that the leader of the free world had intended to deliver at a nuclear disarmament summit—an act of anarchy that doesn’t save the world so much as seal its fate. Pleasence’s president (he isn’t given a name, but remember that the Great Communicator had been inaugurated just six months prior) is an imposter, at a loss for words without electronic mediation—or why else wouldn’t he just read the damn speech live?

Escape did more than put a ding in the Teflon coating. It reunited Carpenter with Russell, the former child actor and future Goldie Hawn co-star/live-in he had directed in the 1979 TV biopic, Elvis. Let’s admit this up front: Russell is a fine comic actor, but for most cinephiles his name is a surefire punchline. (Surely, this is one reason why Quentin Tarantino, who relishes writing comeback roles, cast Russell as Stuntman Mike in Death Proof.) In Russell, Carpenter found the Clint Eastwood for his Don Siegel, not just a workaday actor, but someone confident enough to look stupid or fatuous onscreen. The next two pictures the duo made—The Thing and Big Trouble in Little China—are midnight monuments that have only improved with age.

In a perverse stroke of timing, Universal released Carpenter’s remake of Howard Hawks’s 1951 The Thing From Another World in June 1982, two weeks after E.T. had opened. “Theirs was nice, ours was mean,” Carpenter has said—although he was later responsible for his own cloying alien picture, Starman (1984). The Thing is arguably the creepiest film Carpenter ever made, which is saying something, and the reason is that the setting—a scientific outpost in Antarctica—simultaneously appears realistic and otherworldly. Location shooting was actually done near Juneau, Alaska, but judging by the real South Pole—at least as presented earlier this year in Werner Herzog’s Encounters at the End of the World—Carpenter’s snowscapes, bunkers, and socially awkward men were right on the mark.

In The Thing, a Norwegian crew uncovers a UFO buried in the ice for an eon, unleashing an alien that can mimic any life form by absorbing it. The creature polishes off the Norwegians in the first scene and then infiltrates an American encampment that includes Russell’s hardboiled helicopter pilot, MacReady. At some point-—it’s impossible to say when, although some fans have tried—various characters are “infected” by the parasite (most memorably, Wilford Brimley’s gruff biologist, Blair). Carpenter modulates our point of view, alternating between subjective and objective shots that tend to confuse rather than clarify who exactly has been turned. The Hawks original was a response to McCarthyism, and although Carpenter's version is also the story of a creature awakened from a cryogenic sleep, The Thing is more than just updated political satire. It's a blackly comic vision of modern loneliness, with the extreme-weather setting and microbiological menace presaging our current eco-based anxieties.

The supreme Carpenter-Russell collaboration, however, remains the Orientalist cult phenomenon, Big Trouble in Little China (1986), a critical skunk and box-office flop upon its release. Scripted by W.D. Richter (The Adventures of Buckeroo Baonzai Across the 8th Dimension), Big Trouble was ahead of its time. Its stylized dialogue, plot idiosyncrasies, and cross-cultural irreverence were innovations that contemporary action hybrids like Kill Bill can now take for granted. But what’s striking today is the contrast between Jack Burton, Russell’s protagonist, and the decade’s overtly patriotic multiplex heroes such as Indiana Jones and Rambo.

Although Burton is a walking riff on the stereotypical Reagan Democrat (he’s a truck driver in a mesh cap), Russell plays the character as a clown (he also wears knee-high moccasins and what looks like a Tijuana-acquired poncho). Burton is the only male character in Big Trouble’s Chinatown oblivious to the real score, and unlike his Chinese American friends he has no training in martial arts. He lacks even for ripostes to journalist Kim Cattrall’s screwball verbal onslaught. According to Carpenter, a pre-credit scene was ordered by Barry Diller (then chair of 20th Century Fox) to establish Burton’s white-hat cred (his trucker cap is black and has a Harley-Davidson logo). Diller got what he wanted, but when Burton dons a tweed suit and horn rims to go undercover inside a brothel, it’s hard not to see Russell as parodying Harrison Ford’s self-important professorial Nazi-killer.

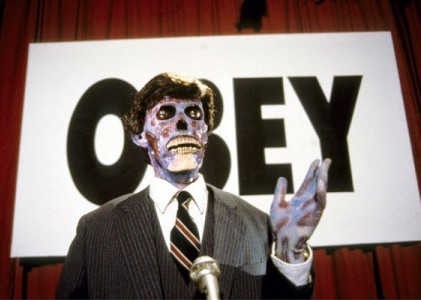

What a pity that Russell—who was working at the time on Robert Towne’s Tequila Sunrise—wasn’t available for the lead role in 1988’s They Live, which went instead to WWFer “Rowdy” Roddy Piper (who, to his credit, at least ad-libs well). In terms of marrying leftist politics to hardcore genre clichés, They Live, the fourth film in BAM’s series, is Carpenter’s magnum opus. In contrast to Escape From New York’s imaginary dystopia, They Live unfolds in contemporary Los Angeles, where a community of day laborers barely subsist together in a shantytown. After the LAPD destroys their slum, construction worker Nada (Piper) joins an underground cell intent on exposing a vast conspiracy among America’s leisure class. The rich, it turns out, are different from you and me—they’re aliens, aided by human beings who have chosen to collaborate for profit. This description can’t do justice to the scene-for-scene hilarity Carpenter extracts out of Nada’s awakening, with the help of special sunglasses, from his false consciousness.

It’s easy to understand why critical favoritism falls on the four pictures in the BAM series, for the same reason that it’s obvious now why Kael was so harsh in her 1978 Halloween review. At the time, Kael was championing more intellectual auteurs like De Palma and Martin Scorsese, directors who made genre pictures that she felt were advancing the art. Carpenter’s style, by comparison, was passé. No one could have anticipated that two years later a Cold War relic would re-popularize the ideology of his youth, and that old-fashioned genre filmmaking would become a natural vehicle for resistance (and not just an opportunity for dumb shocks). The sensibility of The Thing or They Live (or even the underrated 1983 Stephen King adaptation, Christine) was apposite for the Reagan years precisely because it was so retro.

If in the 20 years since They Live, Carpenter hasn’t always sustained the consistency he did throughout the 1980s, his recent work nevertheless deserves reappraisal. As basic as their titles suggest, Vampires (1998), Ghosts of Mars (2001), and Carpenter’s two episodes for HBO’s "Masters of Horror" series, Pro-Life and Cigarette Burns possess an economy and an eccentricity missing from many genre pictures today. At the very least, these movies are far superior to Hollywood's recent Carpenter remakes—Jean-François Richet’s Assault on Precinct 13 (2005), Rupert Wainwright’s The Fog (2005), and Rob Zombie’s Halloween (2007)—which don't shed half the light on the aughts as the originals did on their respective era. The lowbrow Carpenter oeuvre will endure, ultimately, not just on the strength of its former cultural relevance, but because an artfully executed genre film is still something rare. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Morning in America

Morning in America

FURTHER READING

Scott Tobias on They Live (The A.V. Club)Joshua Rothkopf's interview with John Carpenter (Time Out New York)

THE AUTHOR

Benjamin Strong is the film editor of Fanzine and has written about movies for Slate, The Village Voice, Chicago Reader, The L magazine, and other publications.

More articles by Benjamin StrongAuthor's Website: Fanzine