Moments of 2008, Part 2

Moving Image Source launched in June 2008. To commemorate the end of our first year, we invited contributors and colleagues, as well as some of our favorite writers and artists, to select their moving-image moment or event of 2008—anything from an entire movie or TV series to an individual scene or shot, from a retrospective or exhibition to a viral video or video game.

Part 2 of the survey follows. Part 1—including responses from David Carr, Joshua Clover, Guy Maddin, and others—can be found here.

Todd Gitlin, professor of journalism and sociology at Columbia University; author of The Bulldozer and The Big Tent

The first moment is a whole film: Man on Wire. I am someone who wants the sublime even in our understandings of human possibility, thinks we don't have enough of it, or at least not enough ways of depicting it. The imagery of religious transcendence pretty much exhausts the prevailing repertory, and that doesn't swing it for me. I exulted in Man on Wire. I was quite literally on the edge of my seat—when did that last happen at the movies, to me, at any rate? I wept. I'm an acrophobe so I was anxious through most of the film and that didn't matter—or maybe precisely because I could borrow Philippe's audacity for the moment, cheap, the anxiety turned inside out and became sheer joy. The second is actually a still image: the New York Times photo of the Hasidic infant bawling at the funeral service for his parents, who were murdered in Mumbai. If there is an opposite of sheer joy.

Melissa Anderson, film editor, Time Out New York

At the very end of Before I Forget, Jacques Nolot, attired in the worst drag since Jackie Curtis, stands nearly motionless at the entrance to a porn theater that his young trade has taken him to. Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 blasts; Nolot stands—or is that endures?—with defiant, willful abjection. Who or what is he waiting for? It’s a haunting, mordant conclusion to a film that’s brutally honest about aging, decay, humiliation, and loss.

Geoff Andrew, head of film programming, BFI Southbank

Choice one: Rouben Mamoulian retrospective, through December at BFI Southbank. Sheer unadulterated pleasure; terrific films—which look better and better with the passing years—from a supremely cinematic artist who now perhaps might lay claim, sadly, to being the most underrated of all Hollywood directors of the studio era. Not a Hawks or Welles, maybe, but up there with Sternberg and Cukor; and far more than a mere stylist, he's arguably an auteur with a very special and sophisticated take on the sexual impulse. He seriously deserves reassessment.

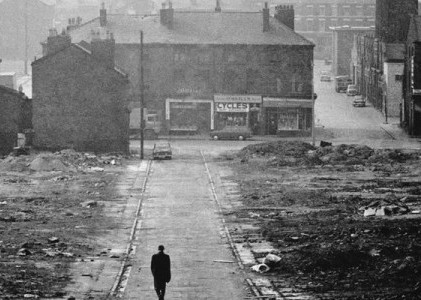

Choice two: the "Folks Who Live on the Hill" sequence in Terence Davies's Of Time and the City. A perfect meeting of (borrowed) sound and (found) image; of the personal and the political; of incredible subtlety and savage irony; and a most welcome return to the fray by a great and (in his homeland) sorely neglected filmmaker.

Adrian Martin, senior research fellow in Film and Television Studies, Monash University; co-editor of Rouge

The exhibition "Correspondences" by Victor Erice and Abbas Kiarostami, in its most complete and updated form, reached Australia in August and enchanted us until November: an extraordinary montage, on walls and floors and across spaces, of video letters and photographs, documents and film excerpts, notes and reflections, memories and fantasies. An unforgettably rich experience.

Miguel Marias, critic and former director of the Spanish Film Archive

Abbas Kiarostami's Shirin conjures with the slightest means the imaginative powers of the audience, to make us "see" in our minds the epic narrative spectacle (one never knows whether it is a film or a stage performance) seen by the onscreen audience (mostly women of all ages, each with beauty of a different kind, and all of them capable of being sincerely moved, naively if you want). This seems to me a lesson both in economy and in emotion, as well as a daring demand for the kind of moviegoers some filmmakers need to go on working.

Molly Haskell, critic and author of Frankly, My Dear: Gone With the Wind Revisited

Notes of male grace in old films that feel amazingly new (both in the Film Society retrospective honoring Manny Farber):

D. W. Griffith's The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912) (with screenwriting by Anita Loos), starring Lillian Gish. Elmer Booth as the "Snapper Kid," charismatic slumdog gangster, a whirling dervish of movement and charm who uncannily anticipates Jimmy Cagney.

Raoul Walsh's Me and My Gal (1932). Spencer Tracy, not yet weighed down by his reputation, is buoyant and aerodynamic as a New York cop who practically dances through his romance with a gum-chewing waterfront waitress played by Joan Bennett.

Alexander Horwath, director of Austrian Filmmuseum

To me, a moment is never just one, or "alone." I'm more interested in the "momentum," a constellation that carries its own charge, distinct from the individual forces that it consists of. My 2008 constellation consists of at least five elements. 1. All the Pieces Matter—a basso continuo that is The Wire, from Season 1, Episode 1 (which I saw on January 1) down to the final episode of Season 5 (which I saw near the end of the year). 2. The Life of Things—a single evening of exhilaration, seeing my favorite film of the year (Summer Hours) for a second time, at "my own place," and talking about it with Olivier Assayas until the wee hours of the morning. 3. If Films Were Lives—12 evenings with Thom Andersen, before, after, and during the screenings of his magnificently transgressive "Los Angeles" film series in Vienna. 4. Love Is Stronger Than Death—the music of Matti Bye for Victor Sjöström's Phantom Carriage, played live by Lotta Johansson, Kristian Holmgren, and the composer, creating a version of the film that made its 19th-century morality speak to me like never before. 5. All That Matters Goes to Pieces—the split-second at the lake in Revanche, directed by Götz Spielmann, when the ex-con Alex realizes that he will not shoot the cop who killed the love of his life.

Saul Austerlitz, author of Money for Nothing: A History of the Music Video From the Beatles to the White Stripes

The final episode of The Wire was, for me, the most anticipated, and the most satisfying moving-image moment of the year. After five seasons of unbearably intimate, astoundingly vivid American life, David Simon sent off his characters—our friends and companions—with style, wit, emotion, and poetic grace.

Michael Atkinson, critic and editor of Exile Cinema: Filmmakers at Work Beyond Hollywood

There was this YouTube video of a girl sitting on her couch with a ukelele, singing Oingo Boingo's "We Close Our Eyes," that made me dream of having had a different life, and the image of Bush ducking thrown shoes, and the aged fear in Mickey Rourke's eyes, and The Mysterious Geographic Explorations of Jasper Morello. But it has to come down to the ghost-ice bootprints on the endless sidewalks of Guy Maddin's valentined hometown, the silhouetted sleepwalkers roaming the city alleys, the train of sleepers that always moves but never leaves town, the frozen racehorse heads arrayed in the snow. Really, the whole hoagie of My Winnipeg.

Jason Eppink, assistant curator of digital media, Museum of the Moving Image

This is the year a video game moved us to tears, crossing that symbolic threshold into (dare I say it?) art, and proving the medium's true possibilities. It was Passage, Jason Rohrer's ambitious game about life, death, and everything in between, lasting exactly five minutes. Rohrer followed up with the equally stunning Gravitation, about the exhilaration and isolation of the creative process, and Between, a disjunctive two-player puzzle where players indirectly affect the progress of the other through various states of "wake" and "sleep." With no traditional endings, few instructions, and vague (if any) success metrics, Rohrer's games quickly turn confused exploration into heady introspection. Finally! No more hand-holding: video games just grew up.

Ed Halter, founder of Light Industry; author of From Sun Tzu to Xbox: War and Video Games

In 2008, I was lured into participating in a political blog by filmmaker Jim Finn, which resulted in spending far too much time trolling the Internet for weird election videos, ranging from the semi-pro to the sub-amateur. My favorites included a late-game recap of the presidential race as a re-dubbed Golden Girls episode, two happy lads who went by the name of The Palin Boys, and one particularly effective takedown of the Republican National Convention simply titled Drill Baby Drill (below). That last one used the convention set's they-asked-for-it monochrome background to chromakey in horror-movie scenes of people being skewered alive on drills while the crowd cheered on the carnage, McCain snickered, and Palin cooed with delight. As crude a statement as you’d ever desire, the video highlighted the ridiculous extremity into which the Grand Old Party had devolved—and provided a mere simulated taste of the all-too-real death and horror that they had wreaked upon the world in the past eight years.

Rob Nelson, film critic, MinnPost.com

The comic pivot point of W., Oliver Stone's times-are-a-changin’ biopic-as-exorcism, belongs to Jeffrey Wright's seething Colin Powell, whose Coalition of the Willing rundown turns the War Room into Comedy Central: “Let’s not forget the 90 Mongolian troops—I hear they’re damn fine wrestlers too.” Runner-up is Stone’s simply cathartic final credit: "The End."

Jonathan Lethem, author of You Don't Love Me Yet and The Fortress of Solitude

For me the ploddingly-directed, shatteringly-moving image of the year was the blue-and-red map taking shape on CNN or MSNBC or wherever on Election Night, a vision I'd rehearsed hundreds of times on an Internet "election-simulator" that filled in the states in an increasingly pleasing way over the weeks before the "real" thing, but could in no way prepare any heart for the consummated vision of triumph that had us all running out into the Brooklyn streets to share champagne and congratulations with neighbors we'd barely nodded at before...

The final episode of The Wire was the only collective event that came close.

Scott Foundas, film editor, LA Weekly

The live images of Jesse Jackson and students on black college campuses across America weeping euphorically as Barack Obama ascended the stage in Grant Park to give his acceptance speech as president-elect. A potent reminder—echoed by the year's two great movies about race, Moving Midway and The Order of Myths—of how resonant the racial divide in America remains for those at the disenfranchised end of the spectrum, and easily the most encouraging sign in decades that entrenched nostalgia for the antebellum South may finally start to crumble.

Mark Asch, film editor, The L Magazine

We watched the election at some friends' apartment, toggling the volumes on somebody’s portable TV on a chair in the corner picking up Channel 13's wobbly over-the-air signal, or the other networks during commercials; a laptop on the kitchen table streaming CNN or MSNBC; another laptop, with a slingbox, hooked up to the TV; and everybody’s own computers, on laps and in bedrooms to check FiveThirtyEight and Senate updates. The big TV was on MSNBC when polls closed in California, and we all left the matrix to take a victory lap around South Williamsburg, shouting back at people shouting down from windows and fire escapes, high-fiving strangers outside of bars, waving at honking cars. We got back in time for the acceptance speech, on three screens, in alternate close-ups and wide crowd shots.

Sam Adams, critic and contributing editor, Philadelphia City Paper

Barack Obama's acceptance speech was more cinematic than most movies, with pomp and circumstance courtesy of a nicked John Williams score (from The Patriot, natch). But the moment that struck me more personally was the Obamas' post-election interview on 60 Minutes. Sitting next to each other, the president-and-first lady-to-be demonstrated a quality exceedingly rare in public figures: genuine mutual affection. I'm so accustomed to the spectacle of public figures performing some mummified remnant of their marriage vows that Barack and Michelle's unforced intimacy felt more radical than any policy he's likely to propose.

Joshua Land, critic and co-editor of Essays & Fictions

For many of us in the U.S., 2008 was first and foremost the year of Barack Obama and the promise of political transformation. The essence of that promise was most movingly represented in the closing-credits sequence of WALL-E, a series of cave drawings that envision a newly ascendant humanity rebuilding the world from scratch with the assistance of a benign intelligence. The ending (accompanied by Peter Gabriel's pointedly titled "Down to Earth") completes WALL-E's complex dialogue with Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey; if Kubrick's film was the final word on the era when technological development began to decisively outstrip humankind's intellectual and spiritual capacities, a problem the film could only resolve by leaving the human race itself behind, then WALL-E heralds the great reboot, the beginning of a technocratic era of human-sized goals—and more modest expectations. We may no longer be reaching for the stars, but rebuilding some roads and bridges would be a nice place to start.

Laurence Kardish, senior curator, Department of Film, Museum of Modern Art

In New Orleans as part of the first American art biennial, Prospect.1, there is a multi-room installation at the Contemporary Arts Center titled Remember the Upstairs Lounge by Skylar Fein. The Upstairs Lounge was a second-floor gay bar in New Orleans that went up in suspicious flames in 1973 with a tremendous loss of life. In one small room of the installation, almost a closet, a monitor replays local television news of the fire as it was happening. Given the outcome, given the future of New Orleans, given the sudden catastrophes New York experienced, the footage is chilling and very, very sad.

Berenice Reynaud, critic and film/video programmer at Redcat

Two shots, one soundtrack. In Jia Zhangke's 24 City, the camera pans over a group of middle-aged women, dressed plainly, standing together. They have spent their lives working for the same factory. Some of them have tears in the corners of their eyes. If they have not been laid off yet, they will be soon. China is switching from heavy and defense industry to what everybody else has been doing: manufacturing computer parts, selling services, generating income through real estate speculation, hoarding other people’s debts. They have become obsolete, and the factory is turned into a luxury condominium called 24 City. Yet they sing. They sing "The Internationale" at the top of their lungs. We cut to another image, the site of the former factory while on the soundtrack the lyrics still promise “the prisoners of want” that they will unite the human race. Then the building implodes.

Like Jia Zhangke himself, I am one of the people once inspired by the words of "The Internationale." Socialist revolution was going to turn the world into a better place. China was on the vanguard of these changes. In two shots, through purely cinematic means, Jia expresses the sense of loss caused by the end of an era, the end of a collective dream, with rare poignancy.

Dennis Lim, editor, Moving Image Source

Though it often feels like a one-woman show, Kelly Reichardt's Wendy and Lucy is very much a film about human interaction—or, more precisely, about how the social contract is broken or upheld in moments of stress and at the margins of society. Down-and-out Wendy (Michelle Williams) encounters plenty of indifference and worse. But the film doesn’t discount the kindness of strangers, most obvious in the form of an elderly parking-lot guard (Wally Dalton) who offers a sympathetic ear and presses into her palm a parting cash gift that a devastating shot reveals to be the grand sum of . . . six dollars. The ongoing season of economic gloom, and the mixed emotions of a year both hopeful and grim, distilled into a single image.

A special mention: the momentous Nagisa Oshima retrospective, organized by James Quandt of the Cinématheque Ontario, and still making its way across North America.

David Sterritt, chairman, National Society of Film Critics; co-editor of The B-List

The event of the year wasn't one occurrence but a series of them—the arrivals of several first-rate political pictures that made it into theaters and may have played some role, however small, in shifting the currents of American thought in ways that paid off in the November election. Some of the best were documentaries: Standard Operating Procedure by the invaluable Errol Morris, who uses photographic images to analyze the potential of photographic images for both evil and the exposure of evil; Taxi to the Dark Side by Alex Gibney, a viscerally effective exposé of government brutality at its illegal and immoral worst; and Stefan Forbes's Boogie Man: The Lee Atwater Story, the latest indelible dossier (following Bush's Brain, The Trials of Henry Kissinger, and others) on a right-wing ideologue drunk with dishonorable power. But most heartening of all is Gus Van Sant's Milk, a triumphant instance of commercial moviemaking put to progressive purposes by a filmmaker at the peak of his powers. May the new year bring us many more like these. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Moments of 2008, Part 2

Moments of 2008, Part 2

KEYWORDS

Terence Davies | The Wire | television | independent cinema | Abbas Kiarostami | internet | Hollywood | video games | American PresidentRELATED ARTICLE

Moments of 2008, Part 1 by Various WritersMoments of 2011, Part 2 by Various Writers

Moments of 2011, Part 1 by Various Writers

More: Article Archive