Lessons in Darkness

“It sometimes seems to me that there are two types of detective novelist. One… is the criminal sort, whose only interest is in the crime and who cannot be satisfied when writing a detective story… unless depicting the cruel psychology of the criminal. The other is the detective type, an author of very sound character whose only interest is in the intellectual process of detection and who is indifferent to the criminal’s psychology.”

—Edogawa Rampo, Beast in the Shadows (1928)

Rampo’s novella comes to the screen as a slithery-paced thriller obsessed with the alabaster body of Lika Minamoto. Barbet Schroeder, its director, is one of those connoisseurs of frayed psychology. He began with stories of people pushed onto extreme precipices by monomaniacal obsession—films that never quite decided if the characters were ruining their lives or perfecting them. Later work charted the subtle process by which little rents of moral compromise stretch open, the inevitable betrayals forced by binary ideas of Good and Evil. His formative masters were Eric Rohmer, whom he worked with, and Fritz Lang, whom he tried to (traveling to India for an ultimately unmade film)—both men who dealt in the formulation of insoluble moral dilemmas.

Schroeder shares a vocational interest in transgression with the attorneys, in various states of ethical surrender, who populate the second half of his career: Alan Dershowitz (Reversal of Fortune), Stanley Tucci’s D.A. (Kiss of Death), Panos Demeris (Before and After), Jacques Vergès (Terror’s Advocate). All these lawyers gratify his passion for blustery personalities, people conscious of how they affect a room when they walk in (even an empty one). The films are a gallery of conscious actors and many hams: General Idi Amin, Bulle Ogier’s maîtresse, Germán Jaramillo’s pederast monologist in Our Lady of the Assassins, Claus von Bülow, Chuck Bukowski.

Dealing with sensationalistic subjects, Schroeder himself isn’t sensationalistic; he recedes rather than announces himself through the enfant terrible bullhorn. (“Everyone finds his style. Mine is to disappear as much as possible. Let the people speak for themselves without a voiceover telling you what to think and give your POV.”) Think of Preminger, who had the same interest in the morals of institutions. His camerawork is increasingly deferential, clearing space for performers; his greatest stylistic extravagance usually comes in scene-setting opening shots—the crane through the Willets Point scrap heaps in Kiss of Death; dropping with the beat into the Barfly honky-tonk; the helicopter sweep over Newport manors in Reversal of Fortune.

***

Schroeder was a junior auxiliary member of the Langlois Cinémathèque gang in the early ’60s, when he attached himself to Rohmer, 20 years his senior, then editor of Cahiers du cinéma. Sparsely contributing to Cahiers, Schroeder realized he wasn’t a critic. But with no talent yet articulated, he had wunderkind ambitions (and perhaps some family money); in 1962, aged 22, he, Rohmer, and Pierre Cottrell founded Les Films du Losange.

A strapping lad (for a cinephile, anyhow), Schroeder starred in Rohmer’s first short Moral Tale (The Bakery Girl of Monceau, 1963); his heavy jaw and faintly Mephistophelian brow has since graced much of Jacques Rivette’s filmography—of which he was a key financier—among other sundry fare (Beverly Hills Cop III!). He performed in Jean Rouch’s entry in the first big Losange production, the anthology Paris vu par, which belongs to history for introducing the Barcelona-born, doubly exiled out-of-work cinematographer-director Néstor Almendros into the New Wave fold. Schroeder, already very much his own man:

Nobody wanted to talk to Néstor because everybody in the French cinema was from the Left and this guy… had escaped from a Communist paradise….There was nobody who wanted to approach him because the cultural thing of the Left was so strong….Néstor was living on a camp bed and eating only Quaker Oats.

The bright young Cahiers polemicists had conceived an aesthetic-moral putsch, but for all their theories, they lacked confederate craftsmen, so DP Henri Decaë was the highest-paid man on the set of The 400 Blows. One of their common meeting grounds was a renewed way of seeing the lived-in world—Rohmer called it returning "back to things themselves"—but this was words on paper without Almendros, who could drape things themselves with natural light that made everything fresh as milk.

Almendros shot Schroeder's debut, More, a dead-end drug vacation starring American exploitation journeywoman Mimsy Farmer and torpid German Klaus Grünberg. Drifting expat twentysomethings meet cute at a Paris pot party, then remove to the outcroppings of the isle of Formentera, where she turns him on to heroin and they nod off trying to live out a bootleg Byron fantasy of metamorphosing from pasty, civilized, uptight Northerners into Mithraic philistines ("I wanted the sun and I went after it. I didn't care if I got burned"). The film may seem to be trying too hard (affected slang, threesomes, macramé pants, genie bottle crashpad décor), but this is natural to a movie about clueless kids trying too hard. Farmer, ostensibly our femme fatale, shucks her clothes in front of a near-stranger as deliberated proof of liberation; behind her peevish moods and pearly little smile is the lost blankness common to well-heeled girls living an out-of-their-depth boho fantasy—it's in Laurie Bird and Jean Seberg too.

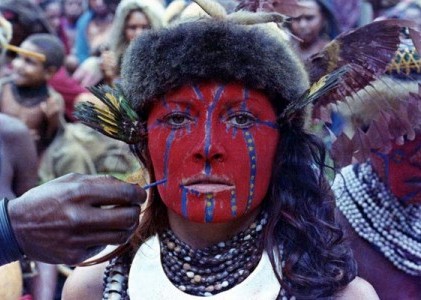

More establishes the story Schroeder returned to over the years: a couple conjoined by obsession, first in a kind of mentor-student relationship, later in a mutual ante-upping game. It endures better than a [typical] freakout dropout time-capsule by chronicling without buying stock in junkie romance and mind-expansion pamphleteering. La Vallée (Obscured by Clouds) largely lacks that protection of ironic remove. It’s Schroeder’s first film with wife-to-be Ogier, here the bourgeois trophy spouse of a diplomat, falling in with a hippie explorer-utopian in upland New Guinea. Stirred by languorous, gauzy longhair sex and Bird of Paradise feathers, she joins his caravan into tribal backcountry, where things dissolve into an indigestible hippie gumbo of Rousseau (Jean-Jacques and Henri), Melville’s Typee, Huxley’s Island, Norman O. Brown, “ethno-voyeurism”… all overlookable when Almendros is wired on plein air, doing scrolling Scope arrangements of flowers and Mapuga headdresses and pale lavender shirts in diffuse morning dew. Ogier’s Edenic head trip, playing opposite a tree and a snake, is the best short film of 1972.

Schroeder, Ogier, and Almendros reunited on a triumphal movie about love amid the upscale s&m tribes of Greater Paris, Maîtresse (1976). Gérard Depardieu is a provincial loosed on the city in country boy buck-stud prowl, wearing second-skin jeans and affecting the rolling gait of a Genet pimp. He’s caught rifling through dominatrix Ogier’s dungeon, a clean neon lockdown where the captive customers wear Christian Schad faces. A face-off begins between this deceptively fragile female predator and her thuggish, lunky kept man, ever scrambling to repair his masculine initiative as it’s ever shredded anew. The film garnered some infamy for documentary-veracious vignettes of Depardieu watching a horse butchery (then buying equine flank steak at a boucherie chevaline) and a masochist customer having his genitals pinned to a plank. What’s remarkable today is not these transgressions, but the familiarity of the story they tell as a scenic amplification of the intrinsic power play in any relationship between strong, stubborn people.

In Tricheurs (1984), Ogier is picked up for a good-luck charm by Jacques Dutronc, looking for a system to break the roulette tables. They begin a sporadic, oft-sexless symbiosis—one drive leaves no room for another. Bleary Dutronc, with his air of flat-seltzer anhedonia, is as natural as upholstery to the game room’s airless interiors (shot by Robby Müller). The film ranges between continents and gambling resorts, its primary arena Oscar Niemeyer’s clean intergalactic casino in Madeira. In a farce of a striver’s tale, our hero begins defeated in a ditch and winds up with a dream castle and a girl—but nothing’s essentially changed, which we understand through Schroeder’s lucent maintenance of tone. The Road of Excess doesn’t finally lead to the Palace of Wisdom; it kills time, at least.

Probably aware he’d grown sluggish in Hollywood, Schroeder left for South America in 2000, fulfilling an old plan: “I've got to find a great Colombian writer who is not a friend of Castro.” His search ended on Fernando Vallejo’s first-person narrative Our Lady of the Assassins, which came complete with the treasured tutorship narrative. Gray literary eminence (German Jaramillo, playing authorial stand-in Fernando) returns to his hometown of Medellín, where he falls in love with rough-trade boys, casual participants in the cartel capital’s routine street gunfighting. Ever-opining Fernando and his protégé-boyfriends perambulate through neighborhoods, churches, cafés, bakeries; it’s a great city film, epitomizing Schroeder’s walkabout location-scouting technique in practice (“When I'm in a town… I draw squares on a map, and then I walk all the streets”).

Staying with the homosocial and homicidal was a contemporized Leopold and Loeb story, Murder by Numbers (2002), with another pair of mutually reinforcing thrill-junkies, here unsupervised high school “orphans with credit cards” stalking tony California coast suburbs. Michael Pitt’s the Nietzsche-highlighting theorist-philosopher, radiating halitosis, with a gelled-down Kraftwerk butt-cut; moon-faced Ryan Gosling’s his second-string-jock disciple. Producer/starlet Sandra Bullock nicely frazzles her anchorwoman handsomeness as a boozy detective, despite the tedious device of teasing at her tormented backstory.

Though universally slagged, it’s a film pocketed with perverse pleasures: an especially flushed and bong-fried Chris Penn, an out-of-nowhere attack ape, a pervasive sense of social collapse. As always, Schroeder adapts pulp with the same deference and seriousness most reserve for tackling Tolstoy. Without a reassuring wink to confirm he’s better than his material, though, the intelligence that’s behind even his tepid commercial works is often overlooked.

Hardly alone among the Cahiers class in his affection for American films, Schroeder actually had the temperament and adaptability to go from Losange to Los Angeles, to be at ease on a “Hollywood” set. His stateside debut in ’78 explored Dr. Penny Patterson’s unprecedented success indoctrinating a lowland gorilla, Koko, with sign language. Conceived as fiction (a potential Every Which Way But Loose competitor), Koko evolved into a tender and slightly screwball documentary, a reportage from the outer limits of consciousness paralleling Herzog’s Land of Silence and Darkness or his Kaspar Hauser film (the two globetrotting filmmakers have sometimes worked along similar lines, through Schroeder engages in none of Herzog’s obtrusive self-promotion).

In L.A. around that time, Schroeder started a relationship with writer Charles Bukowski, in self-imposed exile on his own obscure island of pie-eyed perception. They collaborated on subtitles for Godard; Schroeder pressed Buk for a screenplay. The project’s backstory makes up Bukowski’s Hollywood, where alter-ego Hank Chinaski is passed around by expatriate Euro artistes with transparently-reshuffled monikers. Schroeder (aka “Jon Pinchot”) is recalled living in lethal Venice Beach ghettos with Tricheurs’ inspiration, Steve Baës (“Francois Racine”). The filmmaker observed back, recording Buk in a series of wine-oiled interview-monologues, compiled in 52 bite-sized takes as The Bukowski Tapes. The author emerges as one of the fitfully charismatic, narcissistic monsters Schroeder loves, riffing against pothead apathy and, at one point, bicycle kicking at his wife (On shooting: “Whoever was the least drunk held the camera”).

Barfly wrapped after a torturous eight-year gestation—in Hollywood, Pinchot is depicted threatening to saw off his own finger if a producer won’t cut some red tape. Mickey Rourke did Chinaski, cruising splay-legged like he’s hasn’t wiped his ass in decades and reading lines like a bejowled Brando impersonating W.C. Fields. Whatever you think of Buk’s self-mythology, it’s a remarkable collusion between author and director—an idiosyncratic literary worldview hasn’t been so digested and regurgitated onscreen since the Rand-Vidor Fountainhead. This can lead to overindulgences, like a subplot involving a wealthy, gorgeous academic dilettante trying to lift Chinaski from skid row (the line “it’s a cage with golden bars” is uttered, straight-faced), but what one finally remembers is Rourke’s blowfish strut and purring hot-air, the start-me-up Friday night skronk of “Hip Hug-Her.”

Determined non-participation in the world is the tie that binds Schroeder’s fiction features up to Barfly. The only “work” done is two counts of breaking-and-entering, peddling drugs, s&m sessions, rigging a roulette ball, and playing poetaster on the typer. Chinaski speaks for the Schroeder protagonist: “Sometimes I just get tired of thinking of all the things that I don't wanna do.”

Reversal of Fortune (1990) addresses a different outsider caste: the ultrawealthy, tired from doing nothing. For the first time Schroeder worked on a readymade project, from a nonfiction bestseller by lawyer Alan Dershowitz. The subject was inherently more commercial than ennobling a drunk: socialite Claus von Bülow’s high-profile court appeal, after conviction for his now-catatonic wife’s attempted murder. The case contained all the elements to attract “the public”: an identifiable villain, infidelity, a proof of aristocratic rottenness. Jeremy Irons’s von Bülow is the suspected killer, as impeccably fiendish as a PBS Professor Moriarty, inclined to framing his baronial profile for dramatic effect. Schroeder’s sleight is to make von Bülow, chilled by the desolate luxury of mausoleum mansions, come off no worse than Ron Silver’s Dershowitz, a guilty-liberal opportunist trying to placate his conscience with charity cases.

Schroeder had the honor of losing an Oscar to Kevin Costner, and came out happily situated in the early ’90s, when pseudo-sophistos peddled glacéed cobalt-and-lipstick Hitchcockian softcore around Hollywood. There was a hit with Single White Female (1992). The plot devices are checkout-line paperback silliness—a ventilation shaft transmitting crystal-clear secrets between apartments, a shoebox hiding a concise psychological profile. The decorative baroque lighting over orgasmic writhing on impeccable linens is the stuffing of countless After Dark section VHS tapes. But SWF has survived in the popular imagination—Jennifer Jason Leigh coming downstairs in the salon with a doppelganger of Bridget Fonda’s strawberry bob—in a way that, say, Poison Ivy has not. Much of this is in Leigh’s stormily petulant performance, but also the fact that, in the terms of a potboiler, the movie addresses a set of identity anxieties familiar to many young women. If you’ve ever spent any extended time with teenage girls (sisters particularly), you have heard the assertion “You can’t be me!” at least once. Maybe not high art, then, but a pop-psychology sleepover classic, and how many of those has Godard made?

Turning 50, his career trajectory laid out by back-to-back hits, Schroeder settled into a groove—coasted, if you prefer. There was a 1995 “remake” of the 1947 Kiss of Death, scripted by Richard Price, which had the unfortunate task of shouldering David Caruso’s post-NYPD Blue leading man expectations. It’s a good bridge-and-tunnel brooder with a feel for scratch-off ticket New York, where no grown man seems to have a real full-time job, and his last wholly good movie for a spell.

The first hour of Before and After (1996), Schroeder’s snowed-in prestige psychodrama, swells into a crescendo of real ache. Parents await the return of a fugitive son implicated in murder; when he arrives, it’s dolorous adolescent Edward Furlong, when the actor had the kind of anguished beauty you’d expect to find glowing in marble in the alcove of a gloomy church. The tangled morality of law is revisited with the appearance of Alfred Molina’s Panos Demeris—reminiscent of Leon Ames in Angel Face—to whom a case won is the only truth. But Meryl Streep and Liam Neeson, as husband and wife, gradually smother the movie with acting. Note this is the only nuclear family anywhere in Schroeder’s work, and it shows his helplessness with normalcy, trying to make the stoic virtues of sacrifice and forgiveness compelling.

It would’ve been his worst movie if he hadn’t signed on to Desperate Measures (1998). It’s one of those master-criminal movies featuring a cop looking through a file and saying, “He has a supra-genius level IQ…” The film’s done with such seriousness and concentration, at times it seems Schroeder has actually convinced himself he was making a Langian moral conundrum à la Fury instead of a Neanderthal actioner—this even as he was dutifully filming Michael Keaton sliding down a laundry chute, breaking his fall with a defibrillator.

***

Schroeder’s ability to become an American director, for better and worse, is partway owed to a cosmopolitan upbringing. His father traveled in the oil business, and Barbet spent his formative years in Iran (he was born in Tehran), Africa, and Bogata, Colombia, where he lived from age 6 to 11, during the period of La Violencia, a decade-long machete free-for-all between political factions. Schroeder recalls witnessing fatal street fights then, with the same air of blithe violence of Our Lady of the Assassins.

From his biography, we can assume Schroeder knows German, French, Spanish, and English. He has shot films in Portuguese and Spanish islands, Uganda, New Guinea, Colombia, Cambodia, on both American coasts and, now, in Japan (Paris usually appears in his films only as a waystation or somewhere to be left behind). When Munich became a cinematic capital, Schroeder got closer than his café-bound peers, taking a producing credit on Fassbinder’s Chinese Roulette (he gave RWF vet Kurt Raab a last good role in Tricheurs, which also had Peer Raben on soundtrack duties). Wherever Schroeder’s gone, he’s not been easily distracted—that is, his films have remained fundamentally oriented around characters. In the U.S., he didn’t snap billboards and luncheonettes like a vacationing Euro, but saw just another environment populated by human beings.

A personal linkage to the colonial past has allowed Schroeder exceptional insight in his documentary explorations of its legacy, profiles of President Idi Amin and lawyer Jacques Vergès. Amin recalls the humiliation of Africans acting as beasts of burden for the Caucasian ruling class; Vergès traces back the roots of his subsequent “voice of the voiceless” career: “My childhood memories are of a country where colored people had to step aside to let the Europeans go by.” You empathize: Amin is an imperial figure and must’ve known he was born to rule in a world where might and swagger were the lone determining factors.Vergès is an immensely proud man, and to think back to kowtowing before some podgy, ineffectual consul must be a rankling scar on his ego.

Idi Amin Dada had shouldered into office a couple years before Schroeder touched down to profile him in ’74; he found Uganda a collective hallucination, almost one of those make-believe nutzoid republics encountered in ’30s comedies, Klopstakia or Freedonia. Amin drills his troops for their invasion of Golan Heights, then unwinds by playing concertina at a dance. This linebacker with a boy’s smile is likable until you remember that his whim is law, and a nation of millions has to dance to his tune. In several scenes the future His Excellency President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Amin addresses a roomful of subjects or underlings (the cabinet, the nation’s convened physicians) with unprepared, halting comments, while the audience hangs on every syllable exactly as though they’re terrified of becoming crocodile chum if they don’t. Trying to decide if Amin is stupid or stupid like a fox provides a great deal of the film’s fascination.

Amin’s racist “economic war” and the “disappearance” of uncooperative Ugandans (many reappeared, waterlogged, in the Nile) were already attracting condemnation, but the glow of the postcolonial moment hadn’t fully faded, and true political vilification was largely reserved for holdouts like Rhodesia’s Ian Smith. And so a contemporary write-up of Idi Amin could chide that “no apparent attempt was made to come to terms with Ugandan history or politics as a means of establishing a context for Amin’s overheated prose” (this isn’t true—though it should be noted that establishing a mediating context for slaughter is the stock in trade of Vergès).

Terror’s Advocate (2007) was Schroeder’s first documentary in nearly 20 years, and the movie about 9/11 that was badly needed—it’s all the better for the fact that the WTC isn’t once mentioned. Overstuffed with names, dates, photographs, transcripts, and case histories, it’s a bulging dossier of a movie on (in)famous Franco-Vietnamese defense lawyer Vergès, whose clients and associates (Pol Pot, Klaus Barbie, Carlos the Jackal…) are a Who’s Who of 20th-century political violence. It could be Schroeder’s nod to Dostoevsky’s Demons: “The lawyer who defends an educated murderer because he is more cultured than his victims…the juries who acquit every criminal are ours….When I left Russia, Littré’s doctrine that crime is insanity was all the rage; I came back to find that crime is no longer insanity, but simply common sense, almost a duty; anyway, a gallant protest.” (From Reversal: “All this legal activity, is it in Satan’s service?”)

For Vergès, colonialism is the original sin; once the West is found guilty of this, it can be innocent of nothing else. His trademark trial strategy, debuted in the defense of Algerian FLN bomber (and later wife) Djamila Bouhired, is the defense de rupture, which calls into question the moral authority of the court to pass judgment. He seems incapable of holding any native-born despot responsible for their actions—the closing credits reveal a litany of African dictators among Vergès’s clientele. One imagines that only linguistic barricades have kept Vergès from mixing with the Tupamaros, Red Brigades, or All-American Tim McVeigh.

“A Palestinian is yesterday’s Algerian,” says one FLN veteran and foot soldier in the ongoing struggle, neglecting to note that the European Jew was yesterday’s Algerian. Like Amin, who brandishes a well-thumbed copy of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Vergès’s battle against The Oppressors finally lands him in the precincts of old fashioned European anti-Semitism, consorting with Swiss Nazi-cum-Palestinian libber François Genoud (the specter of Old Apocalyptic Europe floats all through Schroeder’s films: the kids in More get their junk from an exiled sieg heil-er).

The process of portraiture is a coaxing, the gratifying camera bait to draw out the subject’s ego. Terror’s title card accompanies a portrait of Vergès as he perhaps likes to imagine himself: straight-backed, stonefaced, fists clenched, defiant, indomitable. Schroeder never vents open indignation at Vergès, who reinforces his righteous rigidity by pushing back against the sanctimony directed against him; a light touch instead, and just enough rope. Idi Amin Dada is subtitled “A Self-Portrait,” indicating Amin’s careful presentation of what the camera would be allowed to see. Schroeder credited Almendros’s eye for subverting the dictatorial storyboard. The cinematographer had already escaped fascism and communism both—his family had fled Franco’s Spain before Cuba—and knew where to look for the telltale absurdities of despotism (Almendros, who was gay, would later direct a documentary on the imprisonment of homosexuals under Castro—you’ll have to look awhile to find this man’s kind of guts in the contemporary art house).

Schroeder asks Vergès the same question Dershowitz asks himself in Reversal: “Would you defend Hitler?” Vergès: “I’d even defend Bush… but only if he agrees to plead guilty.”

If you laugh at his punchline, who’s the joke on? Terror is a thumbscrew escalation of premises, asking a viewer time and again how much moral equivocation they’re willing to accept. “You realize it is very dangerous to approve anything in the first place,” says Schroeder of the romantic resistance of Vergès’s early cases, herein enhanced by the reenactments of Algerian café bombings from Pontecorvo’s Battle of Algiers. “There is no real difference between [that] and the [twin] towers. There is a logical thread.”

It’s a premise built to discomfit, not to gratify those who look to the movies for affirmation. So Schroeder, the great cosmopolitan, seems determined to keep his bags packed, a man without a country. Too uncommitted (and sometimes heretical) for the Left, too acclimated to decadence for the moralizing Right, just too young for the New Wave, high-toned enough to seem pretentious in adolescent-pandering Hollywood, too phlegmatically Teutonic to seem quite French, and yet never really German to begin with. He’s hard to place, and we often forget about him until the moment his next film comes to town. Yet: Maîtresse, Tricheurs, Reversal of Fortune, Terror’s Advocate… Don’t these look suspiciously like the work of a major artist?

Would Rampo’s hero think Schroeder the “detective” or the “criminal sort”? Or was the very attraction of Beast in the Shadows that it eliminates its narrator’s certitude in a final drop of ambivalence—the gray to which Schroeder always repairs. He is more concerned with the investigation than the findings; the resulting films are dogmatic only in consistently showing little difference, in effect, between the best and worst of intentions. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Lessons in Darkness

Lessons in Darkness

KEYWORDS

Barbet Schroeder | nouvelle vague | Retrospective | Eric Rohmer | Néstor Almendros | Bulle Ogier | Charles Bukowski | Hollywood | Idi Amin Dada | Jacques VergèsTHE AUTHOR

Nick Pinkerton has written about films in The Village Voice, Reverse Shot, and Stop Smiling magazine. He is a product of Cincinnati, Ohio, and currently lives in Brooklyn, New York.

More articles by Nick Pinkerton