Good Neighbors

"Historic time consists only of a past, whose chief claim to superiority is that we're not part of it."

—Hollis Frampton, "Incisions in History/Segments of Eternity"

1.

To get to "Wish You Were Here: The Buffalo Avant-garde in the 1970s," a new exhibit at Buffalo's Albright-Knox Art Gallery, you must enter the museum through a glass vestibule crouched on the east side of Elmwood Avenue, its unspectacular rear entrance rather than the grand Neoclassical Temple front that overlooks Delaware Park, the crown jewel of the city's Olmsted-Vaux park system. Turn left at the admissions desk, and walk down a hallway lined with paintings by some of the biggest names in mid-century Modernism: Marc Chagall, Salvador Dalí, Jean Tinguely, Frida Kahlo. Ascend the heavy marble stairway next to the visitor information stall, and find yourself swallowed up in a Sol Lewitt wall drawing and then spat out into the first room of the exhibit.

There you are greeted by Bruce Nauman's screen prints of squeezed lips and pinched neck fat that make up studies for holograms (a-e) (1970). On the wall to your left are two pristine, hyperreal Ed Ruscha lithographs: Drops (1971) and Lisp (1970). In the glass display cabinet on the opposite wall, the poster for Gilbert & George's Red Sculpture Album (1967) adds another bright hue to the room's loudly clashing colors. The pale glow emanating from the adjacent room issues from Dan Flavin's Untitled (to Donna) (1971), its ghostly neon glare filling the space with an unstable, wavering presence.

Studies for Holograms (a-e), by Bruce Nauman

Next, weave your way around an array of colorful, irregularly sized paintings, drawings, and sculptures by artists like Rafael Ferrer, Hannah Wilke, and Jirí Kolár. Continue past a long white room that displays Cindy Sherman's A Play of Selves (1976). Follow the loud, steady hum of film projectors, punctuated by recorded sounds of breaking glass, and part the heavy curtains to enter the dark, roomy box that contains the four projectors and the speakers producing the racket. Close the curtains as tightly as you can to screen out any leakage from the overhead lights in the other rooms, and take a minute to bask in the overwhelming, sumptuous images and aggressive sounds that make up Paul Sharits's Dream Displacement (1976). One of the multi-projector installations that Sharits called "locationals," Dream Displacement represents a further elaboration of the filmmaker's career-long project to put his spectators in direct contact with the material basis of the cinema, the museum space allowing him now to include the projectors, the mechanical armature of the medium, into the experience of the work itself, no longer forced to just gesture toward it from within the illusion it creates, as he had in his works for the movie theater. Each of the machines projects short loops of alternating, solid-color frames that come together as the loops sync up, and quickly break apart again, momentarily appearing as one large single image on the wall before each frame reasserts its distinctness.

Four-projector, "locational" installation Dream Displacement, as part of Paul Sharits: Dream Displacement and Other Projects

As a film work for the museum and as a multi-format spatial experience, Sharits's installation provides a fitting conclusion to this brief tour of Western art's trajectory from the 1930s through the 1970s. The Modernist monuments passed on the way to "Wish You Were Here" belong to the permanent collection at Albright-Knox, which throughout the 20th century proved one of the country's most responsive museums to the accelerated developments in the visual arts. Founded in 1905 by John J. Albright, an industrialist who made his fortune in Western New York at the century's dawn, what was then called the Albright Art Gallery evolved under the aegis of board director A. Conger Goodyear, who used a generous endowment to acquire bold new works by Dadaists, Surrealists, and photographers long before other museums were biting. He was forced out by the museum's conservative board in 1927, but his protégé Seymour Knox continued his mentor's vision, bringing abstract expressionists, Pop artists, and other postwar innovators to the museum that would eventually bear his name too—lending a little cultural capital to a city that, apart from its world-renowned architecture, remained most closely tied to its food, factories, and sports teams.

The opening rooms of "Wish You Were Here" demonstrate how the museum kept pace through the 1970s with the various roads that lead out of Modernism. The exhibit does not really concern the artists, such as Nauman and Flavin, who visited Buffalo from elsewhere, but those who actually worked in the city, participating in what curator Heather Pesanti calls the "creative ecology that flourished in Buffalo in the 1970s." On top of Albright-Knox, Buffalo boasted six other remarkable cultural institutions around which Pesanti has designed the exhibit: Hallwalls, Center for Exploratory and Perceptual Arts (CEPA), Artpark, the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, and the University of Buffalo departments of English and Media Studies.

Sharits was a faculty member of the latter department, but his appearance in these initial rooms of the exhibit, designed to showcase the museum itself, illustrates how intertwined these institutions became, and how the fine arts world represented by the museum came to devour everything that it had previously excluded. But while Dream Displacement points forward to the linked fortunes of film and visual art, it also draws us backward: its projectors throw large images high on the wall, towering over the beholder like the history paintings in a 19th-century salon. It draws the mind's eye in two competing directions, toward both memory and speculation, the "complementary vanishing points" of consciousness that Sharits's friend and colleague Hollis Frampton identified in "Incisions in History/Segments in Eternity," which is reproduced in the exhibit's catalogue. In doing so, it directs us toward a trembling awareness of the present moment. As Frampton wrote, "The confused plane of the Absolute Present, where we live, or have just seemed to live brings to irreconcilable focus these two divergent images of our experience of time."

Hollis Frampton

2.

Gerald O'Grady founded the Center for Media Studies at the University of Buffalo in 1972, and the following year established its sister institution, Media Study/Buffalo, a regional community media center that held classes, rented equipment, and hosted regular screenings. Given free rein by the rapidly expanding university, which was still flush with state money having joined the SUNY system less than a decade prior, O'Grady hired some of the biggest names in experimental film and the burgeoning field of video: Tony Conrad, the legendary Minimalist musician who also boasted an impressive body of film and performance art; Steina and Woody Vasulka, the husband-and-wife team who had been early pioneers of artist's video,and who had co-founded The Kitchen in New York; James Blue, a documentary filmmaker who had worked across scores of different styles via every imaginable funding arrangement; and Hollis Frampton, the most consequential figure of cinema's 1960s avant-garde, and who insisted O'Grady hire his friend and fellow structuralist, Paul Sharits.

With this impossibly accomplished faculty in place, UB Media Studies quickly became one of the legendary departments that blossomed in these early years of university film study, a peer to Ricky Leacock's MIT Media Lab and the Ken Jacobs- and Larry Gottheim-run Department of Cinema at Binghamton's Harpur College, just a few hours downstate. O'Grady's staff taught classes at both the university and the community center, bringing experienced grad students and first-time film hobbyists alike into contact with their radical approaches to the moving image. On the side, they created some of their best-known works and, thanks to O'Grady's requirement that the program offer film theory classes, they produced reams of writing on film, video, and what Frampton would call "consecutive matters." O'Grady invited emerging media artists from elsewhere to hold guest lectures at the university, participate in conferences, and present their work at Media Study/Buffalo, whose schedule was filled out by programmers like Thom Andersen and Bruce Jenkins, the latter a Media Studies grad student, among other major artists, writers, and teachers like Kathy High, Keith Sanborn, and Robert Haller, to name only those who appear in the exhibit.

O'Grady's two media studies institutions have received the museum treatment before. In 2006, ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany mounted Mindframes: Media Study at Buffalo 1973-1990, an encyclopedic retrospective that included a digital archive of hundreds of artworks and writings produced by the Media Studies faculty, much of the latter reproduced in its exhaustive catalogue, Buffalo Heads. Situating Media Studies within the larger Buffalo arts community, "Wish You Were Here" features only a fraction of the material that appeared at ZKM, and this wide-angle approach is invaluable. As Sharits's appearance in the Albright-Knox section of the exhibit demonstrates, the Media Studies faculty participated in many other institutions, and the formal and theoretical directions they took during this period are inextricably bound up in this fact.

3.

Albright-Knox was matched in both institutional weight and experimental proclivity by the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, which, like the museum, had for decades been planting the seeds for Buffalo's artistic efflorescence. These efforts paid off in the 1970s, as visionary director Lukas Foss, and his successor, Michael Tilson Thomas, lured the likes of John Cage, Terry Riley, Milton Babbitt, and even the Grateful Dead to the Philharmonic on a regular basis. Morton Feldman's 1971 arrival at UB's music department solidified the city as a center of experimental music.

At the University, Media Studies and Feldman's music department joined a nationally renowned English department whose faculty included Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Leslie Fiedler, John Barth, and a young J.M. Coetzee. This murderer's row of groundbreaking literary talent was supplemented by regular visits from Donald Barthelme, Dwight MacDonald, Allen Ginsburg, and Amiri Baraka, as well as drop-ins from the fixtures of the school's likewise astonishing French department like Michel Foucault, Hélène Cixous, and René Girard. Outside the bounds of the university's suburban campus, a complementary grassroots poetry movement sprang up in Buffalo, with its own distinct array of organizations, reading series, chapbooks, and zines.

While these large institutions provided the financial and structural base for the city's cultural renaissance, much of the era's artistic activity took place at small non-profit community centers, many initiated by the artists themselves. The focal point was Hallwalls, a gallery, performance space, and studio/residence complex housed in a decommissioned ice-packing warehouse on Essex Street. Founded in 1974 by Charles Clough and Robert Longo, painters who had dropped out of art school, Hallwalls attracted a core group of residents that included Longo's then-girlfriend Cindy Sherman, Diane Bertolo, Michael Zwack, and Nancy Dwyer. This group formed one of the bases of what would become Douglas Crimp's generation-defining 1977 "Pictures" exhibition, which included some of Longo's iconic Men in the Cities prints. Crimp's revision of the "Pictures" group in 1979 added Sherman to the mix, her Untitled Film Stills having gained her notoriety in the meantime. Clough and Longo were surprised to discover how readily their artistic heroes responded to Hallwalls' invitations, and the visitors represented in "Wish You Were Here" include such now canonical figures as Dan Graham, Vito Acconci, Jack Goldstein, and the Kipper Kids.

The founders of Hallwalls

The same year Clough and Longo created Hallwalls, Robert Muffoletto, a veteran of Rochester's Visual Studies Workshop, founded the Center for Exploratory and Perceptual Arts (CEPA) in a storefront just across town, a gallery and lecture hall intended to serve as a laboratory for new directions in photography. Like Media Studies/Buffalo, CEPA provided instruction and equipment to curious locals, and exhibited work by Western New York's photographic talent. Their aesthetic and community interests merged in the mid-decade CEPA Bus Shows, for which Muffoletto convinced the local transportation authority to temporarily display work by CEPA photographers in place of advertising, including those by CEPA regulars Bruce Jackson, Ellen Carey, and Cindy Sherman.

Eyes 2, by Charles Clough

Forty minutes north of Buffalo, in Lewiston, there was Artpark, the massive outdoor home for a state-administered artist-in-residence program and summer arts festival, set on acres of toxic industrial landfill overlooking the Niagara River Gorge. Artpark's mandate encouraged the kind of environmental Land Art appropriate to its setting (the first season was dedicated to Robert Smithson), but its first executive director Dale McConathy and his immediate successors opened the doors to practitioners of every imaginable visual- and performing-arts medium, establishing the organization as a wildly interdisciplinary venue that brought the local community into contact with some of the era's most radical aesthetic experimentation. The park's rules stipulated that all work had to be removed at the close of each season, clearing the ground for the next year's residents. "Wish You Were Here" presents documentation and the surviving remnants of Artpark projects from artists as varied as Martin Puryear, Gordon Matta-Clark, Ant Farm, Catherine Jansen, Nancy Holt, and Charles Simonds.

Artpark

4.

With all this cross-fertilized aesthetic experimentation in one place, it is tempting to think of the 1970s Buffalo scene as an avant-garde movement. Pesanti refers to it this way in the exhibit's title while noting in her catalogue essay that the term had become unfashionable during the era in question because of the teleological, essentially Modernist, assumptions implicit to its usage. Artists in Buffalo, as elsewhere, were attempting to dissolve the barriers between the art world and everything else that was once outside its gates, in an effort to bring new media into the gallery context, as at Hallwalls, and to push old ones into other contexts, as at Artpark or in the CEPA bus shows. This widening of art's borders made it not only ideologically distasteful to speak of an avant-garde but also practically unfeasible: with soldiers prowling so many different fronts, it becomes difficult to say who is leading the charge.

The effect is clear in the new directions taken by the filmmakers working at Media Studies. The boundary between the film and fine art worlds was dissolving; Media Studies filmmakers like Sharits, Frampton, and Conrad had emerged in the 1960s, when the divide was more or less absolute. Though all three were accomplished polymaths who had migrated to film from other art forms, and all made films that reflected their engagement with the contemporary concerns of other fields, they operated at this time within cinema's distinct tradition. The film avant-garde in which they participated was self-consciously constituted on the basis of a (perhaps mistaken) narrative of historical development. But the nearly simultaneous advent of video and the beckoning interest of the art world undid the nominally coherent trajectory at the head of which these filmmakers had placed themselves, forcing them to change their strategies or assume new priorities.

"Wish You Were Here" offers a striking material representation of the 1970s art world's appetite for film and video. Before you even reach the Media Studies section at the back of the floor the exhibit occupies, you will have been inundated with moving images. Nearly every room is flecked by video monitors casting the medium's cool light. Many of them serve merely as documentation, in the thin, soupy indexical register provided by early video, of the flurry of activity in the city four decades ago. What Lucy Lippard called the "dematerialization of the art object" (in a book that served as a bible to the Hallwall's gang; Charles Clough's copy sits in a cabinet at the exhibit) had continued apace in Buffalo. Video was the perfect tool for artists to give lasting form to their live, performative and conceptual efforts, and also for those who wanted some means of memorializing their transient installations at places like Artpark. In the Hallwalls section, tapes display performances by Longo, Dan Graham, and the Kipper Kids, all of which seem designed to play equally on their liveness and their future life as recording. Uncredited recordings that depict the installation of Albright-Knox shows "Four for the Fourth" (1976) and Rafael Ferrer's "SUR" (1977) not only offer entrancing portraits of the era's freewheeling, unorthodox energies, but also suggest an art world analogue to the rambling "street tapes" that heralded video's arrival in the United States a decade prior.

Video's formal register—its oddly distended temporality, its liquefied spatiality—is thrown into relief by contemporaneous efforts made on film. At Artpark, Gordon-Matta Clark produced Bingo x Ninths (1974) on 16mm as a companion to Bingo (1974), one of his building cut-outs, the six-foot-long remainder of which slices through the exhibit's large central room. The film's thoughtful compositions and logical editing create an experience distinct from the unblinking gaze of the videos here. Likewise, Charles Simonds three 16mm films Dwellings (1972), Landscape/Body/Dwelling (1973), and Dwellings Winter (1974) picture the creation of his obsessive, ongoing "dwellings" project, structuring the process and interweaving it with the reactions of passers-by: a contextualizing procedure not unlike traditional documentary.

Bingo, by Gordon-Matta Clark

The more elaborate film and video projects made at Artpark and Hallwalls manifest some of the effects of the old divide between the fine arts and experimental film. Though artists from other domains had begun to adopt some of the tools of cinema's avant-garde, they generally did not take on its concerns. Many saw moving image media as a chance to engage Hollywood, whose products reflected contemporaneous fixations on identity and identification, narrative sequence, and referential appropriation. At Artpark, Lynda Benglis and Stanton Kaye staged and produced The Amazing Bow-Wow (1979), a 30-minute Portapak burlesque melodrama about a freak-show-owning couple and their main attraction: a 7-foot-tall, talking, hermaphroditic dog. Their on-the-fly production travesties cinema's narrative codes, but declines to engage its formal ones. Cindy Sherman's early 16mm trifle Doll Clothes (1975), a stop-motion game of paper dolls on which she has pasted an image of her own face, is also inclined toward film semiotics rather than form—like the film-referential series that would establish her and Longo as two of the biggest artists of the 1980s.

5.

If the exhibit's other rooms illustrate how deeply film and video had penetrated Buffalo's larger art community, the Media Studies rooms reflect the film- and videomakers' complementary involvement with other visual art forms. The back rooms contain as many photographs, hanging painting-like objects, multi-format installations, and sculptural spectacles—the accoutrements of the expanded cinema—as they do single-channel works.

Most of the monitors that do not make up parts of larger installations display work produced by students or visitors: Kathy High's Cow Film (1978-'79), three Super-8 shorts by Barbara Lattanzi, and Sara Hornbacher's Numerical Studies: Rutt Cube Interface (1977) from the former group; and Bill Viola's Memory Surfaces (1977) and Gary Hill's Soundings (1979) from the latter. This arrangement fits the exhibit's spatial ambitions, and its portrait of a mutating cinema, but it disserves the underappreciated James Blue, whose ceaselessly curious, assured experiments in documentary are only hinted at by the short excerpts here.

There is only one projected film: Hollis Frampton's Gloria! (1979). It sits alone, between two floor-to-ceiling curtains that section-off the middle of the Media Studies rooms, running on a loop so that every 10 minutes, the back of the museum fills with the wheezing sounds of "Lady Bonaparte." Dedicated to the artist's grandmother, Gloria! spans the earliest days of cinematography to the computer-generated future, like Dream Displacement, forcing a wall-eyed look to Frampton's twin horizons: the 19th century of his grandmother's birth and the 21st century whose approach this new technology heralded, and the slippery present between; the plastic materiality of film and the numerical abstraction of the computer (and video); the machine age and the digital one; life and death; memory and speculation.

Frampton pursued both frontiers during his time at UB. He never fully embraced video but was fascinated by the possibilities of computers. The computer-generated text in Gloria!—which can be found along with several other Frampton films, on Criterion's new DVD set, A Hollis Frampton Odyssey—is a result of some of the research at Media Studies' Digital Arts Lab, which Frampton had founded with Woody Vasulka as a test lab for arts-oriented software and hardware. He also remained deeply engaged with early and proto-cinema. He resumed his career in still photography, working occasionally at CEPA, and with his wife, the photographer Marion Faller. Sixteen Studies From VEGETABLE LOCOMOTION (1975), made with Faller, is a parodic inversion of the logic in Muybridge's animal locomotion sequences, pointing to the legerdemain already present in these earliest stirrings of cinema.

Image from the Untitled Film Stills series, by Cindy Sherman

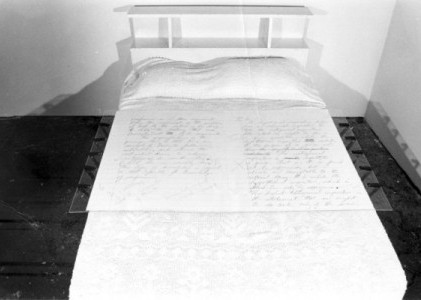

Dream Displacement was not Sharits's only effort to put film to painterly uses. His Frozen Film Frame Series (1971-'76) are long strips of colored 16mm pressed between two thick slabs of Plexiglas and hung from the ceiling to allow light to shine through from both sides. Hanging nearby are his studies for the series, drawn on graph paper in colored ink, with help from Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo among others—drawn films whose relation to the film paintings Sharits called "absolute."

Study for Frozen Film Frame of "Frame Study 15," by Paul Sharits

Frampton, Sharits, and Tony Conrad had previously worked in films along structuralist-materialist lines. These pursuits were thrown off course by the moving image's changing structure and material, and the works at Albright-Knox represent their different attempts to adapt. Frampton and Sharits continued working with film, but Conrad, who had made what was perhaps the most rigorous attempt to grapple with film's foundational ontology in The Flicker (1965), jumped ship for video, performance, and installation. He joined the UB faculty in 1976, invited to teach video by Woody Vasulka, who believed his wide-ranging intelligence would enliven the program's video workshops (even though Conrad had never before used a video camera). He plunged into the new technology and the theoretical literature, working across Buffalo institutions to create works that probed the dynamic between artist and audience. His room at the Albright-Knox exhibit recreates his 1979 Hallwalls installation Come To, a collection of objects that cast his relationship with his beholder in the terms of sado-masochism. Other works are inserted into this disquieting space, including Tiding Over Till Tomorrow (1979), an elliptical narrative in large, panoramic slides. At the entrance to the room a couch and a set of chairs suggest a lower-middle class, suburban family living room, facing a television monitor than runs a loop of some of Conrad's single-channel videos: an excerpt from Concord Ultimatum (1977), and Come On In (1986), a playful later work made long after the era surveyed here, both encircling his interests in narrative, apparatus, and viewer relations.

Examinations, by Tony Conrad

Having worked with video in non-theatrical spaces for many years prior to their arrival in Buffalo, Steina and Woody Vasulka had provided the background against which Conrad and other converts' video explorations unfolded: their early examinations of its hypnotic, consuming effect on its viewer (they initially dubbed The Kitchen the "Live Audience Test Lab"), and its obscure material foundations. At UB, Steina, who had called her work "an analysis of space, or even a surveillance of space," continued exploring the medium's potential for participatory, bodily sculptural arrangements. Allvision (1976), comprising a rotating arm with two closed-circuit video cameras attached, both facing a large mirror ball, slowly consuming all 360 degrees of the room in the image it sends to the two television monitors on each side of the machine, takes the eyes on a zigzagging tour through the panoptic representation, and forces the body into a dance with the apparatus that catches you in its sights no matter where you stand. Allvision is a material instantiation of Woody's later observation that "once you start connecting systems together, they become autonomous and we become their guests."

Allvision, from The Vasulkas / Steina: Machine Vision, Woody: Descriptions

As the filmmakers moved in other directions, video artists inherited some of their materialist appetites, making work that queried the new medium's abstracted properties. The episodes that make up Hill's Soundings borrow the shape of structuralism's cause-and-effect narratives. But it was Woody Vasulka who most avidly posed structuralist-materialist questions within the domain of video. As Conrad tells it, "Woody had become interested in the idea that the key to the substance, identity, and manipulation of the video image lay in the structure of each single pixel on the screen, and that the structure could be best addressed by looking at it as a digital number." His Descriptions (1978) are photographs of video raster scans. Two short single-channel videos, Reminiscence (1974) and C-Trend (1974), present Portapak footage transformed by the Rutt/Etra synthesizer into an alien topography of the video signal.

6.

Pesanti has stuffed this huge restaging of 1970s Buffalo's artistic landscape. with so many consequential works and suggestive histories that it offers countless roads—sprawling highways and shadowy dead-ends alike—through art's past and future. The above is an attempt to travel only one of them. You could spend days wandering through its nooks and crannies, locating all the artifacts of the past and intimations of the future. Visiting it is like getting a chance to explore an old (Art) World's Fair. The merging of film and video, cinematheque and gallery, that was undertaken at this time in Buffalo and elsewhere created the confusion of terms with which we still must operate today: the conditions that have defined moving image experimentation in the three decades since.

Pesanti's inclusion of Frampton's "Incisions in History/Segments of Eternity" at the end of the catalogue is a masterful concluding stroke. One of Frampton's most direct, wide-ranging meditations on the nature of the photographic image, it reframes the essential connections between art-making and death, and between history and the indexical image, as paradoxical collisions that that give us access, however fragmentary, to an ecstatic, timeless eternity. His typically prolix, referentially dense musings articulate the simultaneously exhilarating and morose feeling that the exhibit stimulates. Frampton alludes to "the exquisite stasis of tableau vivant," and Pesanti's three-dimensional portrait of the era can be experienced in the terms Frampton outlines: a present-tense resurrection of a moment that we are continually reminded has long since passed.

Beneath the art history lie the depths of urban and political history. By the time these artists briefly reanimated its cultural life, Buffalo was already living under a death sentence. The creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1954 routed around Western New York all the shipping traffic that fostered its industrial preeminence. Larger structural changes to the American economy would further destabilize the city's livelihood, and Buffalo has yet to recover. But while we usually associate the kind of postmodern cultural expression on display in "Wish You Were Here" with the neoliberal regime to come, Buffalo's creative ecology was nourished by the largesse of the American welfare state at its zenith. Those institutions that were not, like SUNY Buffalo or Artpark, administered directly by New York State, drew their resources from the generous coffers of tax-funded agencies like the NEA and, especially, NYSCA, whose grants were structured to encourage incorporation and upstate location.

The exhibit's title refers to an ironic postcard-shaped painting that Diane Bertolo made for Hallwalls' 1977 "Snow Show," mounted during the catastrophic blizzard that paralyzed the city and has come to seem a grim natural foreshadowing of its chilly economic future. The painting's expression of ironic resignation is doubled by its role here, underlining the mournful longing behind the exhibit's insertion of some of 1970s Buffalo's creative energies into the present day, a longing whose deeper resonances make it more than simple nostalgia.

"Wish You Were Here: The Buffalo Avant-garde in the 1970s" is on view at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery through July 8, 2012 ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Good Neighbors

Good Neighbors

RELATED CALENDAR ENTRY

March 30–July 8, 2012 Wish You Were Here: The Buffalo Avant-garde in the 1970sKEYWORDS

experimental film | exhibition review | New York | Hollis Frampton | Paul Sharits | Albright-Knox Art Gallery | painting | Tony Conrad | Steina and Woody Vasulka | academia | photography | Cindy Sherman | Robert Longo | Charles Clough | video artistTHE AUTHOR

Colin Beckett is the Critical Writing Fellow at UnionDocs in Brooklyn. His writing has appeared in Cineaste, The Brooklyn Rail, BOMBlog, and Idiom.

More articles by Colin Beckett