Going Places

In toto, Gus Van Sant might be the most troublesome American filmmaker working—if we decide beforehand how we will choose to define contemporary auteurism, and if we insist on filmmakers manifesting their ostensibly singular personalities in an at least nominally singular fashion. Surely, Van Sant would scoff at such assumptions. It is certainly not the responsibility of a working artist to conform to post-Sarris notions of how an oeuvre should be shaped, any more than it's a requirement that a filmmaker be interested in only one kind of statement, one kind of voice, one kind of style.

But how do we talk to the Two or Three Heads of Gus Van Sant? For every distinctive masterwork, we have a Miramax-ish crowd-pleaser. Of course the lines can not be quite so sharply drawn—populist smashes like Good Will Hunting (1997) have a jaunty energy that seems lovably Van Santish; idiosyncratic "personal" films like Last Days (2005) and Paranoid Park (2007) seem, to me, like opaque indulgences; no one else could've made Milk (2008) with the same amount of esprit and texture, but I'm still not sure it needed to be made at all. As Van Santians go, I'm both conflicted and picayune, and the blame perhaps lies with his four authentic masterpieces—Drugstore Cowboy (1989), My Own Private Idaho (1991), Gerry (2002), and Elephant (2003)—which place the bar often out of Van Sant's own reach, and together still hold the most profound promise for American art film visible on the horizon.

One can resist the Syd Field-flowchart shape of Van Sant's more commercial films, including the still odd remake of Psycho (1998), but the radical differences seem mostly a matter of visual invention, indelibly American grain, and moving mise-en-scène. When he is operating in his most inspired mode, Van Sant nails down a landscape of experience as distinctively as Fuller, Bergman, Antonioni, and early Scorsese once did. Drugstore Cowboy, coming first after his little-seen freshman film Mala Noche (1986), announced Van Sant with unique authority, striding through a saturated northwestern fringe world as if we all grew up there and knew it was useless to hope for escape: the shabby rented houses and plain-walled motel spaces with curtains drawn, occupied in golden mid-day (when everyone else is working), imbued with the electric fun of being a kid hiding out from the grown-up world and, in this case, tantalized by the prospect of getting high, with the door locked and no worries in sight.

The movie's primary vocabulary is ants-in-the-pants montage, with a smellable fidelity to time and place, and a Fulleresque urgency that gets you right under the sweaty shirts of the jonesing characters, squatting down in a lost highway corner of the country and pursuing in coveted privacy their childish notion of heaven. This was an America we hadn't seen on film before—although it's an outlying neighborhood not far from the backroads of Scarecrow (1973), the wintry barrooms of The Last Detail (1973) and the messy blue-collar yards of A Woman Under the Influence (1976). Every shot of the film is iconic; nowhere do you catch Van Sant lapsing into disinterest, or straying from his belief in the images' supremely tactile mojo.

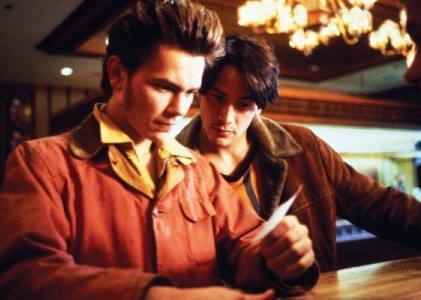

Of course Van Sant has always been fascinated with and sympathetic to social outsiders—gay teenagers, junkies, working-class orphans and wanderers—but the why is more interesting: because if your characters are off the grid, they are then liable to be intimate with the country for real, intimate with its untraveled roads, forgotten towns, and ghost-town industrial centers. Not for nothing are these four films the roadiest of road movies, a context that helps reveal My Own Private Idaho as the last quarter-century's most adventurous and heartbreaking portrait of existential American insignificance. "I know this road...," as River Phoenix's passive, narcoleptic hustler mutters to himself in the middle of nowhere—this film too is an effortlessly iconic torrent of movie isotopes and blooming meanings, from the opening dream-montage (clouds, Slim Whitman, giant tourist-statue cowboy, salmon vaulting upriver) to the final, Rossellinian crane shot on probably the very same road, the circle around the Earth that Mike the Sleeping Boy-Toy finds himself "on," as hamsters run pointlessly on their wheels.

With these two movies, Van Sant had arrived at a new, restless, experimental style and stance that we thought could save American film from itself.

Certainly, by the time you've reached the end of Idaho, you've seen a totally different state-of-things and did so through a sausage machine that took parts from Cassavetes, Godard, Wenders, Beckett, Shakespeare (and Joseph Chaikin?), Makavejev, Richard Lester, Monte Hellman, Robert Frank, and many more voices, and twisted the results into something simultaneously pitiful and wry, self-knowing and naked, concrete and breezily metaphoric.

But of that Gus, that's all we got. You saw signs of him arise amid the formulas of Good Will Hunting and To Die For (1995), but for most intents and purposes that loopy, gritty nascent style vanished, like a runaway on the interstates. Perhaps Van Sant felt drained of it himself—and felt ready for a new injection. Which came with a single viewing of Béla Tarr's Sátántángo (1994), demonstrating with a penitent's resolve how to forge a mise-en-scène universe that was as daunting as it was inescapable, followed up with Tarr's Damnation (1988) and Werckmeister Harmonies (2000). In a MoMA catalogue essay on the occasion of a Tarr retro in 2001 Van Sant admitted a manifest influence. "I find myself attempting to rethink film grammar," he wrote, "and the effect industry has had on it."

It's strange to think how many films busy directors don't have the time or sometimes the inclination to see—Tarr, after all, is merely the newest heir of a 50-year-long tradition that runs at least from Kalatasov to Jancso to Angelopoulos to Sokurov. Be that as it may, Gerry is a mad, devilishly conceived Rorschach blot, just as doped on long camera set-ups (adopting the follow-behind Steadicam march of Tarr) as on narrative inexplicability.

Perhaps we can simply call it a Beckettian parody of both a buddy movie and a wilderness-survival adventure (complete with repetitive chant-like dialogue bytes), because to take it much more seriously than that is to risk drawing architectural diagrams of air. The film is so studiously emptied out of plot signifiers and "events" that its very existence, tempting unsuspecting audiences with its above-the-title use of Matt Damon and Casey Affleck, can seem like an extended gag.

But of course it ends up being far more than that, at least as a temporal experience, just as Van Sant knew it would—something like a shrugging grunge remake of Antonioni's The Passenger (1975), reduced even further to a protracted consideration of Antonioni's last long traveling shot out the window, through the courtyard, and past the off-screen essentials of the story, in a questioning hunt for something else, some other thing that cinema can find or do. For Van Sant, the exclamation point came late in the film, in a dawn-shrouded somnambulism that evokes Beckett's "Ghost Trio," and lasts almost seven whole minutes...

You cannot watch this in silence and conclude that Gerry is a joke, or that the film's inhospitable subtractions don't bear chilling, mysterious fruit.

Elephant, by contrast, is heavy with plot-stuff, crossed timelines, and narrative arcs, all subtly evoked and, in fact, pungently expressed by the Tarr-ish hallway stalks that form the film's infrastructure. It seems as if up to a full 50 percent of the film is spent simply walking, searching behind oblivious teenagers for answers to questions that we know, because we remember Columbine, will be asked.

In a stroke, Van Sant found a way to Americanize and narrativize Tarr's elliptical movements without plunging into obscurity and without sapping them of their force field of mystery and philosophical weight. The high school sense memories evoked are stinging, but the movie's conjugal relationship with the real deal of the Colorado massacre make it resonate even when nothing much seems to be happening. Elephant also seemed a way ahead—we could imagine Van Sant attacking any number of modern conundrums and tragedies and exploring them physically with his camera, reacquainting us with our own ugly handbuilt landscape and our own self-destructing privileges. He could've become our Balzac.

But something else happened. As obsessive and visionary as these films seem, Van Sant also always professed an affection for mainstream feel-good cinema, never felt the need to abate his interest in beautiful young skater boys, thoroughly enjoyed imitating Hitchcock shot for shot, and perhaps didn't want to be pegged as the American Tarr, or, really, as anything else. Cinephiles are defined by their cinephilia, their love, but in some cases we must take a more dispassionate view, and accept that filmmakers do not always want to fit into the categories we've assembled for them. Gus is Gus, which means, for him, that he is not his old films. If Restless (2011) doesn't bring you a Gus you can use, maybe just wait. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

THE AUTHOR

Michael Atkinson is the author/editor of six books, including Ghosts in the Machine: Speculating on the Dark Heart of Pop Cinema (Limelight Eds., 2000), Flickipedia (Chicago Review Press, 2007), Exile Cinema: Filmmakers at Work Beyond Hollywood (SUNY Press, 2008), and the novels from St. Martin's Press Hemingway Deadlights and Hemingway Cutthroat.

More articles by Michael AtkinsonAuthor's Website: Zero for Conduct