Garden Party

The Venice Biennale is on display from early June until November, but in the first four days, the art world descends on the impossible city like, well, art world vultures on plates of canapés. This is not the best time to go to Venice: the regular ratio of locals to tourists must at least be doubled (making it about 1:200), so even with the contemporary art market suffering an economic setback, the main pavilions and Daniel Birnbaum-curated "Making Worlds" exhibitions located in the Arsenale and the Giardini are overcrowded and generally unpleasant places to be (to say nothing of the art). In this full-blown, sheets-to-the-wind art sprint—a sprint, however, mediated by water boat—surely the greatest casualty is film and video work. In a city of impatient neurotics, who has the time to concentrate on the moving image? But this cinephile didn't mind: it gave me a chance to rest my aching feet.

In talking to (and overhearing) Biennale regulars, two general conclusions were confirmed. First, the quality of projection for film and video work continues to improve, enabling projections to be more varied in their presentation than ever. No longer is film or video in the art world confined to the black box; rather, work was projected onto multicolored sheets of canvas (Ulla von Brandenburg), small screens built into standard white walls (16mm projections from the wry Portuguese metaphysicians Gusmão and Paiva), exposed brick (Paul Chan), and the omnipresent freestanding canvas or LCD monitor (most everyone else). In the case of mad scientist of the arts Simon Starling's terrific Wilhelm Noack oHG, the dazzling, intricate 35mm projector itself is the invention, and its very making is the subject of the film it is constantly projecting.

Second, what happens in Venice often comes from Venice. This year especially there was an excessive amount of work, non-video included, that took as its starting point the actual starting point of its creation, often to the point of distraction. Even the favorite of the curator cognoscenti (and runner-up to Bruce Nauman for the Biennale's main prize), the Danish and Nordic pavilions by Elmgreen/Dragset, incorporated a kitschy oil painting of the same pavilion in the off-season, looking like some Mulholland Drive summer palace. Their deconstruction of domesticity, The Collectors, relegated the moving image to television; in a destroyed Danish bourgeois home, a weird children's show played, while next door, in their fabrication of a gay art collector's modernist house, a nubile lad lounged on the carpet and watched William E. Jones's The History of Gay Pornography. (I assume the bodies are rotated over the next few months.)

The most anticipated and discussed work came in the British pavilion, where newly minted cineaste Steve McQueen re-entered the art world to divisive reactions. For every critic who claimed he "phoned it in," there were others who proclaimed his piece the single best work in the entire Biennale. Perhaps the reactions stem from the source—the former being a cranky New York Times art critic, the latter coming from a major North American film festival programmer. McQueen's work more than ever seems to straddle these porous boundaries. During the opening days of the Biennale one had to reserve an advance booking, then sit for over half an hour (!) in a makeshift theater (!), no late entries or exits allowed. (This led more than one observer to call the British a bunch of fascists.)

McQueen's "phone call" from a local area code, a double-screen projection matter-of-factly titled Giardini, posits what happens in the gardens of the Biennale during off time: for McQueen, it's like a dilapidated film set, if not a Tarkovskyan zone, strewn garbage and foraging hounds included. McQueen associates this dilapidated state with colonialism, and the history of the gardens: initially built by Napoleon as part of his conquest of Venice, they're now used for a vestigial remnant of nationalist competition (on par, say, with the World Cup). Trudging through the packed Giardini, one might forget that these buildings were erected as structures of national power. McQueen just shows the exteriors, and often zooms in to the flora and fauna of the gardens, the flowers and the bugs beneath one's feet, treating them more artistically than biologically. And at night, somewhere out of the darkening mist, two men—one white, one black—magically appear, and, at one point, embrace. In a way, one can also say he's made a Tsai Ming-liang film, though I doubt the art crowd got that connection—knowing his audience, McQueen referenced the Venetian sunsets of Turner.

On its own terms—which are admittedly somewhat limited—Giardini is a success. If it's a phone call, it's one where the numbers are dialed very, very slowly. I don't believe there's any raging sense of anger behind the camera, more of a contemplation; it's political art that surrenders itself to beauty. (A more rabid and foaming assault on colonialism came in Luxembourg's thundering Collision Zone, a sturm und drang, J.G. Ballard–influenced, blue-filtered multiroom immersive experience from Gast Bouschet and Nadine Hilbert that was just as bug-obsessed.) In the end, though, Giardini makes most sense if one watches it in Venice itself, having trudged through the exact same geography beforehand, being aware of the specific spatial relationships between shots—and then immediately re-entering that space after viewing. The effect is seeing the gardens anew, almost ignoring the sometimes gargantuan pavilions plopped in their midst.

Giardini will surely travel, but the same cannot be said of Dorit Margreiter's film shot inside and around the Austrian pavilion, the slightly more unimaginatively titled Pavilion. Pavilion is what you get—in this case, one with actors preparing to shoot some kind of scene inside, and, liberally sprinkled throughout, Margreiter's own sculptures. A film about the space of an art exhibit, especially the one that you're sitting in, can come across as a bit insular, to say the least. Margreiter's mildly surreal work pales next to McQueen's as an exploration of the Giardini and its buildings and also suffers in comparison to Singspiel, a tangentially similar, also black-and-white film in the Arsenale by Paris-based German artist Ulla von Brandenburg.

Instead of the palazzos of Venice, von Brandenburg elected to shoot in Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye outside of Paris, and transmutes the Savoye family's actual experience of "ideal living" into a winding, seamless, approximately 15-minute take of domestic anxiety. She stages various types of performance in quizzical (and, appropriate for Le Corbusier, mechanical) fashion, accompanying the action with her own voice on the soundtrack, singing two deathly severe songs composed for the film. It's hard for me to explain exactly what goes on in the piece, and I suspect I'm not alone, but this tinge of mystery helps rather than hinders the projection. Both works—von Brandenburg's especially—are filmed (on 16mm) and staged with such precision and Teutonic seriousness that at times the films threaten to cross over into downright art-film parody, but, hey, I think the same thing about Michael Haneke.

Elsewhere, artists ventured outward—into their native lands—and delivered national representations of various quality. The Welsh gave their off-off site over to erstwhile musician John Cale, who opts to explore his national identity via a five-screen installation of a breathless and rather boring hike through the Welsh highlands in winter. In the Irish pavilion, Kennedy Browne presented a smart multiformat installation on globalization featuring a Google mistranslation of a Milton Friedman statement on the free market ("There isn't a single person in the world who could make this pencil") and one hell of a pencil-sharpening marathon overlooking a uniformly gray Dublin from high atop Liberty Hall, a labor union landmark. And in the Canadian outhouse, Mark Lewis, a Canadian living in the UK, delivered Cold Morning, four projections—in a space suited for none—three set in downtown Toronto and one in an anonymous everyplace.

Lewis's seemingly simple urban projections are themselves dialectical, and best considered in pairs. One of the most beautiful pieces I saw in Venice, Nathan Phillips Square, A Winter's Night, Skating, is "simply" that: two lovers ice-skating at night in front of Toronto's city hall. The piece's calm charm derives from Lewis's old-Hollywood-style use of rear projection, which is used to completely different effect in The Fight, a kind of Jeff Wall photograph come to life, where the jostling of antagonists in the foreground goes unnoticed to the rear-projected passersby in the background. (In the Venice rush, a number of the curators I spoke to didn't even catch the rear projection, which was also the topic of Lewis's off-site 40-minute documentary Backstory—an inventively filmed, detail-oriented interview with the Hansards, the first Hollywood family of said cinematic device.) The other two videos deal with diverging perceptions of the city in a more direct manner: TD Centre, 54th Floor is shot from high above the street looking down from the Mies van der Rohe skyscraper, while Cold Morning is a close-up view of a homeless person trying to warm himself on a frigid winter morning, who, one might conclude, is situated at the bottom of the vertiginous shot from above.

But the most surprising work happened to take off from, of all things, cinema, and came from, of all places, Singapore. Naturally situated far off the main drag—and one floor above Iceland—the Singapore funhouse (another awards runner-up) tackles the notion of national identity, structured as a tribute to the golden age of Singapore movie going, with various posters and photographs of cinemas from a private collector, Wong Hang Min (also interviewed in one of the short documentary-fiction hybrids on view from Sherman Ong). But the feature presentation is directed by Ming Wong, who along with an older piece wherein he himself re-enacts scenes from the films of iconic Malay director P. Ramlee, exhibits two inventive and rigorous melodrama mashups—In Love for the Mood and Life of Imitation—with both pieces accompanied by lavish, old-fashioned one-sheets designed by Singapore's last remaining movie poster artist.

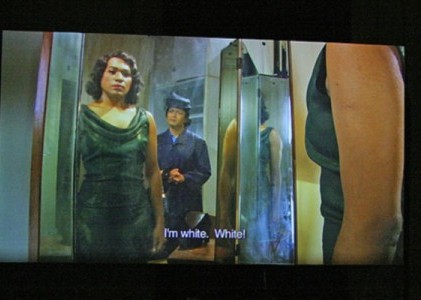

In a more forthright manner than Lewis, who has spent his career examining various apparatuses that constitute the vocabulary of cinema, Wong's pieces aggressively expose artifice, how filmmaking is constructed—here, the emphasis is on acting. In In Love for the Mood, Wong simultaneously plays three progressively accomplished rehearsals for a scene from that other Wong's film, with a Caucasian actress from New Zealand simultaneously playing both Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung's roles. Each scene is subtitled differently—by the time the third and most relaxed performance is shown, the subtitles are in Italian. (The piece is further complicated by the fact that the scene is the one from In the Mood for Love in which Cheung's character is herself rehearsing to accuse Leung's character of adultery.)

But the pièce de résistance comes with the two-screen installation Life of Imitation, Wong's superb restaging of a single scene from Douglas Sirk's melodrama. Undoubtedly also influenced by Todd Haynes, Wong transposes Sirk's issue of race in America to Singapore, casting three male actors of the main national ethnicities (Chinese, Malay, Indian) as Sirk's mixed-race daughter and black mother in their teary farewell scene—recasting the roles with each cut within the scene. Two versions of this scene, shot on a bare-boned set, can be seen contemporaneously, with a well-placed palazzo mirror enabling viewers to switch their gaze between the two, so that this funhouse of shifting identity—both national and personal—resonates even more. Life of Imitation may sound highly distancing, but it's a subtle piece, one that's endlessly fascinating to watch. I can't imagine a clearer statement on the deconstruction of identity and the universality of cinema. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Garden Party

Garden Party

KEYWORDS

experimental film | exhibition review | Venice Biennale | Douglas Sirk | Singapore cinema | video artist | colonialism | Steve McQueen | Ulla von Brandenburg | Mark Lewis | Ming WongTHE AUTHOR

Mark Peranson is the publisher and editor of Cinema Scope.

More articles by Mark PeransonAuthor's Website: Cinema Scope