Domestic Disturbances

Of all the husband and wife filmmaking teams to emerge throughout cinema history, clear a special place at the table for Frank and Eleanor Perry, who burst onto the scene in 1962 with the immensely successful David and Lisa and went on to make five more features and two short TV films before their divorce in 1971. She wrote; he directed. Even so, they made an odd combination: The Ohio-born Eleanor was 16 years Frank’s senior and had a previous marriage and two prior careers, as a suspense novelist in the 1940s and as a playwright in the 1950s. He was a Young Turk filmmaker, born and raised in New York and often spotted with long hair and love beads. This oddest of marital and artistic alliances created some of the most sensitively drawn films of the 1960s—films that have not lost their power after all these years, even if they are rarely mentioned today.

A shame, too, for they made quite a few waves at the time: David and Lisa was an early example of a truly independent, low-budget American film that scored with both critics and the public. (It won a major prize at the Venice Film Festival and garnered Oscar nominations for director and adapted screenplay.) Today, the Perrys are probably best remembered for The Swimmer, their 1968 adaptation of John Cheever’s classic short story—ironic, perhaps, given that the film was a critical and financial flop, and Frank was replaced as director during post-production by Sydney Pollack, who reshot much of it. (On his own, Frank may well be best known for 1981’s Mommie Dearest—for all the wrong reasons, sadly.)

Eleanor held a Master’s degree in psychiatric social work, and the eight films she and her husband made together—many of which focused on extreme personalities—certainly display uncommon psychological acuity. But they also possess a remarkable degree of emotional delicacy, thanks to Frank’s carefully modulated approach to performance (a result, perhaps, of his background in theater). Somehow both clinical and sensitive, the Perrys’ work represents in some senses a missing link in American cinema, coupling the emotional melodramas so popular in previous decades with the emerging ironic sensibilities of the New Hollywood. Indeed, as the collaboration developed, these films moved from simple, audience-friendly tales of human connection to a darker vision of a society beginning to eat itself alive.

Nursery Rhymes and Humanist Fables: David and Lisa, Ladybug Ladybug, and A Christmas Memory

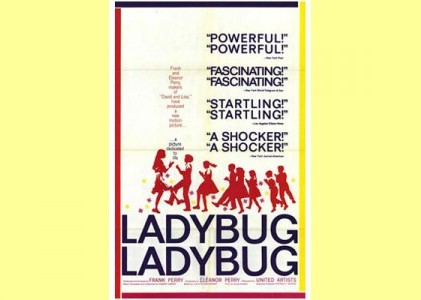

Children’s games often seem to govern the world the Perrys depict: In David and Lisa, based on Theodore Isaac Rubin’s novel, teenage mental patient Lisa (Janet Margolin) can only speak in a strange, rhyming sing-song, and fellow patient David (Keir Dullea), an obsessive-compulsive who cannot bear to be touched, connects with her by emulating her repetitive, rhythmic way of speaking: “Don’t touch, don’t touch. All else will do, but please no such.” Repetition and children’s games are also right up front in Ladybug Ladybug (1963) about a group of primary-school teachers and their students coping with a possible nuclear attack. While the film’s plot recalls any number of Twilight Zone-style stories that were common during this time, it concerns itself mostly with portraying the kids’ attempts to understand the world of adults as their nervous teachers march them home from school.

Of course, these very same adults—both the onscreen ones and the offscreen ones who may have just set in motion the destruction of civilization—are the ones who lack maturity. While the kids show genuine responsibility and compassion for one another, the adults remain lonely, aloof, often unable to communicate their feelings; one teacher, left behind at the school, resorts to silently playing with the kids’ abandoned toys in the break room. The film’s final image is also its most haunting: As the rumblings of what could be a rocket or a plane drown out everything else on the soundtrack, a young boy shakes his fist in anger at the trembling skies, repeatedly yelling, “Stop!”

Although it wasn’t a success, Ladybug Ladybug has dated less than David and Lisa today – perhaps because of its refusal to indulge in typical Cold War suspense. Still, for all their psychological precision, both films offer simple examples of mid-century American humanism. The Perrys’ work would soon take a darker, more unsettling turn—but not before they adapted, to great acclaim and a couple of Emmys, Truman Capote’s Yuletide chestnut “A Christmas Memory” for ABC TV in 1966. Narrated by Capote himself, it relates his Depression-era memories of baking fruitcakes every Christmas with his developmentally challenged older cousin Sook (Geraldine Page).

It’s a beautiful little film, thanks in no small part to a sublime and heartbreaking finale where, over footage of the two cousins flying their new kites on Christmas Day, Capote’s narration reveals that they would soon drift apart, with Sook writing him letters every Christmas—until finally she no longer could. A Christmas Memory (as well as its 1967 follow-up featuring the same actors in the same parts, The Thanksgiving Visitor), with its recollections of holiday rituals and a character others would deem slow, crystallizes the humanist perspective of the earlier films—in particular their fondness for childlike figures.

Dark Games in a Spectral World: The Swimmer, Last Summer, Trilogy, Diary of a Mad Housewife

The Swimmer, about a middle-aged suburbanite (Burt Lancaster) who decides one day to make his way home by swimming through his neighbors’ pools, is the first of the Perrys’ films without any kids in starring roles. Until one realizes that Ned Merrill is a kind of child—certainly, this swimming endeavor is the sort of thing only a kid would attempt. And this strange game, built like so many other childhood games on repetition (each pool offers a different vignette and new characters), will eventually reveal darker truths about its player: his betrayals, debts, and deceptions. The closer he gets to home, the less Ned seems like the healthy, beloved specimen of suburban manhood presented in the film’s opening scenes. Still, this is no ordinary indictment of homo americanus. The surreal finale has Ned arriving at his abandoned, decaying house. His family has long since departed, and the gates are closed. Crouched and whimpering at the locked door, our hero turns out to be a pathetic, delusional man: all this while, we’ve been watching a film about psychosis.

The Swimmer might be the Perrys’ best remembered film today, but it presents a difficult case for study, chiefly because it’s hard to tell where Frank Perry’s work ends and Sydney Pollack’s (and possibly even others’) begins. Perry once speculated that about 50 percent of the film wasn’t his. (We do know for a fact that scenes featuring Barbara Loden as Ned’s former lover were replaced with Janice Rule playing the part—reportedly on the recommendation of Loden’s own husband, Elia Kazan!)

Kids take center stage once more in Last Summer (1969). Adapted by Eleanor from Evan Hunter’s novel, it may be the darkest of the Perrys’ collaborations. It also makes for a fascinating contrast with the ostensibly apocalyptic Ladybug Ladybug, for it unfolds as a series of games and rituals whereby its three teenage heroes—Sandy (Barbara Hershey), Peter (Richard Thomas), and Dan (Bruce Davison)—gradually learn about sex, deception, and cruelty. In their central rite, each of the kids offers a “major truth” about him- or herself, a process that leads to the devastating final scene, when the three rape Rhoda (Catherine Burns), a shy, unglamorous young girl whom they’ve taken into their confidence.

Almost like filmed psychological experiments, Last Summer and The Swimmer both take place in extremely self-contained worlds. One can’t help but think that, as in Ladybug Ladybug, there are unseen forces bearing down on these narratives. The kids’ parents are often mentioned and never seen in Last Summer, and much of the dialogue in The Swimmer concerns Ned Merrill's non-existent family and job. For her part, Sandy also appears to share some delusional DNA with Ned: earlier in Last Summer, after she and her friends nurse a wounded seagull back to health, she savagely kills it for pecking at her, then replaces it with another gull and pretends nothing happened.

The dark coming-of-age fable of Last Summer returned the Perrys to the critical fold after the failure of The Swimmer. They followed it up with an intriguing omnibus film: Trilogy (1969), constructed out of three Truman Capote stories, the last one a slightly edited version of “A Christmas Memory.” The juxtaposition is striking. Although “Memory” has lost none of its power, its nostalgic glow stands in stark contrast to the grim mood of the other two stories: in “Miriam,” a lonely, aging governess (Mildred Natwick) who clings to the illusion that she is still a beloved nanny, discovers an odd young girl (Susan Dunfee) who may or may not be an incarnation of her younger self. In “Among the Paths to Eden,” a middle-aged man (Martin Balsam) visiting his wife’s grave is engaged by a shy, awkward woman (Maureen Stapleton), who later reveals that she came to the cemetery to find herself a husband.

The sad yet likable characters of Trilogy possess an ordinariness that Sandy in Last Summer and Ned in The Swimmer didn’t. But how telling that even in their depictions of mundane characters, the Perrys were drawn to such borderline personalities. A similar paradox governs their final collaboration: Based on a novel by Sue Kaufman, Diary of a Mad Housewife (1970) is a domestic drama about a Manhattan housewife (Carrie Snodgress) who, frustrated by life with her childish, social-climbing husband (Richard Benjamin), strikes up a curiously unfulfilling affair with a hot young writer (Frank Langella), even though he clearly doesn’t think much of her. Although the title implies all the somber clinical precision of the earlier films, for once Eleanor’s script opens up to let the rest of the world in: Diary is a surprisingly expansive film, and its full-blooded portrait of a marriage on the rocks feels a lot more realistic than their somewhat more hermetic earlier work. It’s also worth noting that although the Perrys had always been based in New York City, Housewife is the only one of their films, aside from one of the episodes of Trilogy, to be set there.

Perhaps this time the material hit too close to home: The Perrys’ own Manhattan marriage would end the following year—bringing to an end one of the most remarkable filmmaking collaborations of the 1960s, right at the time that they had begun exploring more personal, immediate territory. Despite some high-profile credits and another Emmy, Eleanor struggled to find a foothold in a film industry that had once embraced her, before her untimely death in 1981. Frank too would die early, in 1995. (His touching 1992 documentary, On the Bridge, is an intimate account of his experiences with cancer.) But in the immediate wake of their separation, he at least would continue to helm bigger films, albeit with diminishing returns. (The mind reels at the psychological acuity Eleanor might have brought to something like Mommie Dearest.)

Coda

The Perrys’ brief run would yield one final, bitter fruit: In 1979, Eleanor penned Blue Pages, a savage and fascinating novel devoted in part to a lightly fictionalized, remorselessly unflattering portrait of her years with Frank, with plenty of potshots along the way to thinly veiled stand-ins for the likes of Capote, Lancaster, and The Swimmer producer Sam Spiegel. The Frank Perry of Blue Pages (called “Vincent”) is a talented filmmaker who is also hopelessly vain, insecure, and, finally, cruel. Still, one comes away from the book not necessarily disliking Frank Perry the person, but feeling sad that Eleanor was so hurt by him as to feel compelled to portray him in this way. She may well have gotten the last laugh: Thanks to the leanness of any significant scholarship on Frank Perry, Blue Pages is probably the closest thing to a book about him that we’ll ever have.

Why did the Perrys’ films begin to slide into obscurity? One might have expected the American filmmakers of the 1970s to embrace these films’ psychological acuity as well as the independent circumstances under which most of them were produced. But perhaps even the Perrys’ later films were too nostalgic for the times—not because they hearkened back to earlier eras (they didn’t), but because they represented a dark lament for a privileged world at twilight. Full of neurosis but devoid of grit, their world is the world of the suburbs, of Long Island and Greenwich, and of the peculiar species of human found in such isolated realms. Lizzie Francke, writing in The Observer, once noted that The Swimmer “captures the schizophrenic mood of late-1960s America—as one nation burned, another cooled off by the pool.” That other nation remains unseen—but it’s hard not to imagine it there in the margins, prodding the Perrys on their journey from warm humanism to the mad despair of a world on fire. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Domestic Disturbances

Domestic Disturbances

FURTHER READING

Guy Flatley's interview with the Perrys (The New York Times/Moviecrazed.com)Johnny Ray Huston on Frank Perry (San Francisco Bay Guardian)

Frank Perry obituary (The New York Times)

Eleanor Perry obituary (The New York Times)

THE AUTHOR

Bilge Ebiri writes about film for New York magazine and Bookforum. He is also the director of the feature film New Guy (2003).

More articles by Bilge Ebiri