Certified Copyright

While walking along the riverfront drag in Phnom Penh earlier this year, I was confronted by what my Catholic educators would have called "an occasion for sin." No, not that occasion, but a seduction that for a film geek is just as tantalizing: a well-stocked bootleg DVD shop, with all the latest Hollywood releases, back-catalogue classics, and spiffy box sets. Having been a long time without cable, I ducked in and asked the girl behind the counter whether she had a copy of Season 1 of The Killing. "Danish or American version?" she asked without missing a beat. For three bucks American, I got 20 episodes on four discs, in mint condition.

Conspiring to rip off Hollywood's prized properties has been a popular practice of merchants and moviegoers since the dawn of cinema, but the rise of digital technology has ratcheted up the stakes from the nickelodeon pocket change of the early part of the last century to the billions of dollars siphoned off in the present one, a fact that makes Peter Decherney's Hollywood's Copyright Wars: From Edison to the Internet (Columbia University Press), a splendid new study of the legal, technological, and aesthetic wrangling over motion picture copyright wrongs and rights, particularly timely. Decherney, an associate professor of cinema, English, and communications studies at the University of Pennsylvania, tells a story that is less about media larceny than media morphing. He views the raging turf wars over motion picture property rights as prime indicators of a communications revolution a-borning. "It is in the debates over piracy that we can see the new media breaking away from the old," he argues. In a daisy chain concatenation, a new medium (cinema) feeds off an old one (theater) and on down the line: television off cinema, home video off television, and the ravenous Internet off everything. Moreover, for all the indignation and lawsuits, Decherney concludes that the vampire who seems to be feeding off Hollywood's blood is more usually pumping an infusion of new energy into the revenue stream.

Cover of Hollywood's Copyright Wars: From Edison to the Internet

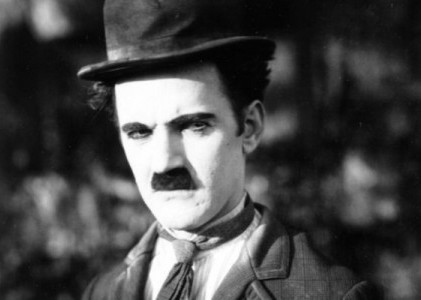

Actually, the operative metaphor is piratical not vampiric, with lawful copyright holders painting violators as scurvy buccaneers who should be hanged from the highest yardarm. "There have been many attempts to abandon these metaphors over the centuries, but they persist," Decherney notes wearily. The author reminds us that, from its earliest days, the motion picture industry was thick with cutthroats swinging in to grab a share of the new media booty. Thomas Edison, the industry's first mogul and monopolist, stole from French prestidigitator Georges Méliès and Edison in turn was ripped off by the shameless Philadelphia pilferer Siegmund Lubin, the Sean Parker of stone age cinema. A low-tech process known as "duping" was a favorite hustle, wherein exhibitors simply copied a print from their competitors and sold it as their own. Other examples of larceny include the unauthorized adaptation of popular novels and stage plays (Harriet Beecher Stowe was a favorite inspiration) and the outright cloning of the acts of popular entertainers (Charlie Chaplin was impersonated by mimics such as Billy West and "Charles Aplin," who brazenly lifted his derby, cane, toothbrush moustache, baggy pants, and gags).

Charles Amador, a.k.a "Charlie Aplin"

As would prove the pattern over the next century, the courts were tasked with untangling the plaintiffs from the litigants and setting the ground rules for the unruly contestants. The intricacies of copyright case law can be tough going, but not the least of the virtues of Decherney's book is that the play-by-play recounting of the legal battles never gets bogged down in lawyer-talk and appellate briefs. Equally at home with auteur theory and tort law, the author provides lucid recaps of the apt cases and offers a balanced appraisal of each side, acknowledging both the intellectual property rights of the creator (or more often copyright holder) and the need for a generous fair use doctrine in a democratic culture dependent on the open circulation of ideas.

A landmark court case over the unauthorized adaptation of Lew Wallace's Ben-Hur decisively changed not only copyright law but the shape of the motion picture industry. In 1907, the Kalem Company, a member of the Edison film trust, released a biblical epic entitled Ben Hur that appropriated everything from Wallace's biblical bestseller but the hyphen. Harper and Brothers, the book's publishers, and Klaw and Erlanger, the Broadway producers who had dutifully paid for the theatrical rights, promptly sued. After the usual circuitous path through the American judicial system, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. decreed that film, being a medium "only slightly less vivid than reflections from a mirror," warranted both the respect of an art—and the fiduciary responsibilities of a business. Henceforth, filmmakers had to pony up for their source material. "The decision resulted in the immediate alliances and eventual vertical integration of publishing, theater, and film industries," argues Decherney, who sees the decision as nothing less than the true "parent of the entertainment conglomerates of the twentieth century."

By bringing certainty and stability to the rough seas of early film traffic, the Ben-Hur decision facilitated the transformation of a wildcat business into the mature oligarchy that was the classical studio system. To be sure, Hollywood was a tempting target for litigation (hence the ubiquitous disclaimer that the characters in the forthcoming photoplay are purely fictional and bear no resemblance to actual persons living or dead), but the Hollywood cartel was too efficient a business model to squander its best creative energies in court. The old studio moguls preferred to keep most of the haggling in-house, letting professional associations like the Screen Writers Guild and the Directors Guild adjudicate screen credit and dispense percentages. When television entered the picture in the 1950s, the studios continued their time-tested strategies of risk aversion. Writes Decherney: "After fifty years of fighting to define the place of film in copyright law, the film industry had similarly learned to avoid courts through a watertight system of exchange based on contracts."

A more subtle literary-legal matter also bedeviled the Hollywood story machine: how to determine which elements of a film are generic and in the air (and therefore, like oxygen, available to all) and which are film-specific (and therefore owned by an author and copyright-able). "The Hollywood studio system was based on plagiarism just as the early film had been built on piracy," quips Decherney, but even plagiarists need some editorial guidance. In order to distinguish "common genre elements (ideas) from original contributions (expression)," the courts eventually devised a rule of thumb called "the scènes à faire doctrine," a common sense guidepost that recognized that tropes like showdowns, cattle rustling, and golden-hearted saloon girls were common to all westerns but that a scenario was John Ford-specific when a group of frontier newspapermen decide to "print the legend" rather than reveal the identity of the man who really shot Liberty Valance.

Two technological innovations—both of which put the means of motion picture reproduction in the hands of the people—reshuffled the deck for the cozy insider traders. First, the commercial entry of the VCR in 1975, when Sony released its consumer friendly Betamax, allowed the average spectator, for the first time in moving image history, to capture, preserve, and share programming. Caught flat-footed, the studios failed to beat back the video incursion both in the courts (Universal's ill-conceived suit against Sony in 1984 upheld home recording as fair use) and in the legislature (by the time the studios got around to lobbying Congress for taxes on blank videotape, Americans looked upon home taping as a constitutional right, with or without the express written consent of Major League Baseball). Besides, the ancillary profits from video rental and purchases turned out to be a windfall for Hollywood. Why restrict a technology that is making you a fortune?

The second and far more serious threat/opportunity is the ongoing digital revolution. Here, however, entertainment conglomerates saw the Jolly Roger on the horizon. The result was the infamous Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) of 1998 (nicknamed by detractors the "Mickey Mouse Protection Act" because Disney is such an aggressive rat-bastard in protecting its brand), a legislative coup that gave the motion picture industry the kind of legally sanctioned technological stranglehold it had coveted since the age of Edison: a federal law making it illegal to break the digital firewalls and copy a DVD or Blu-ray. "Since 1998," as Decherney puts it, "Hollywood has both made the locks and holds the keys." The stern FBI warnings that come onscreen before a Netflix evening—threatening five years in prison and fines of $250,000—put the full force of federal law enforcement behind Hollywood's business model. Of course, enforcing the law, especially in regions beyond the jurisdiction of the FBI, is another matter.

FBI's Anti-Piracy Warning Seal

Still, unless you are a commercial bootlegger or host a peer-to-peer website, motion picture copyright law is surprisingly supple and reasonable—and actually more generous than is commonly supposed. Thanks in no small measure to Professor Decherney's own congressional lobbying, media professors can screen clips and even entire films in a classroom setting without asking for or paying permission. Most artistic and journalistic appropriations of copyrighted material are also protected. The catch is that tales of ruinous lawsuits and cease-and-desist letters cast such a chilling effect that artists and scholars are often cowed into overcompensating: erring on the side of extreme caution, asking for permission when none is needed, balking at an aggressive exercise of their own rights of expression. "[It] is often in the interest of large media companies to remain silent and preserve the ambiguity of the fair use doctrine," notes Decherney. Surveying the recent literature, the author discovered only one case of outright suppression by a copyright holder: Todd Haynes's Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1986), the unauthorized biopic of the singer featuring an all-Barbie and Ken doll cast, whose use of entire songs by the Carpenters drew a cease-and-desist letter from Richard Carpenter—but no lawsuit either from the Carpenters' music label, A&M, or toy manufacturer Mattel. Decherney's bottom line on fair use is to either use it or lose it. Here the author walks the walk: the customary copyright credits for the illustrations in his book are conspicuously absent.

Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story

One caveat: I wish Decherney had spoken more about the moral and generational part of the equation in the digital age: how young people who would never shoplift a Blu-ray from Target have no qualms about burning and downloading copyrighted material, indeed who take a rebellious delight in breaking down firewalls and spreading around other people's work. In 2004, when a seething Jack Valenti, just back from China with a briefcase full of bootleg DVDs, arrived at MIT to speak at a communications forum, the raucous undergraduates in attendance came dressed as buccaneers, complete with fake parrots and plastic cutlasses. They rasped a defiant "Arg!" as the president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America spoke passionately of the sacredness of intellectual property rights and their role in a free society. For his part, Decherney is sanguine about what the film industry sees as a crisis of multibillion-dollar proportions, seeing the theft of digital product not only as unstoppable (the hackers will always find a way to outsmart the gatekeepers) but as "a natural part of the development of new media" and a salutary part at that. "Piracy, history tells us, is often just a name for media practices we have yet to figure out how to regulate."

Perhaps—but whether as a legacy of my analog roots or Catholic education, I still feel a twinge of guilt about my own ill-gotten DVD booty. When it came time to get Season 2 of The Killing, I purchased the box set on Amazon, fair and square. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Certified Copyright

Certified Copyright

KEYWORDS

digital media | distribution | book review | FBI | copyright | Hollywood | auteurism | technology | Peter Decherney | studio system | VHS | DVDTHE AUTHOR

Thomas Doherty is professor of American Studies at Brandeis University and the author of Hollywood's Censor: Joseph I. Breen and the Production Code Administration (Columbia University Press, 2007).

More articles by Thomas Doherty