Key Man Agonistes

"Dread," claimed Norman Mailer, "is that anxiety that you can't name." His is the most compelling definition of the condition that I have ever heard: "You wake up in the morning and you just feel that it's going to be a terrible, terrible day, and you can't say why." Mailer was ostensibly discussing Picasso (for whom work, Mailer said, kept dread at bay), but the protagonist of The Nickel Ride—a two-bit gangster named Cooper—would know what he is talking about as surely as any artistic genius. As the film begins, Cooper lies awake in bed at some god-awful hour in the brightening morning, and the only time we see him sleep in the entire film is when he is having a nightmare. In the last scene, we think he might be sleeping, but that would be to confuse death for sleep.

Picasso had his paintings. Cooper tries to stave off his dread through omens and talismans. It is curious that The Nickel Ride, recently released on DVD, is so preoccupied with such things: before even one frame of film was shot, the project seemed to be cursed. George C. Scott agreed to star as Cooper, but "he got sick, or something happened," as screenwriter Eric Roth recounted to Patrick McGilligan in Backstory 5. After the film premiered at Cannes in 1974, according to Village Voice critic Tom Allen, the studio chose to remove two key scenes. For director Robert Mulligan, fate was particularly ruthless. The Nickel Ride came on the heels of an extraordinarily productive period in his career—it was his eighth film since 1965—but following its failure at the box office, it would be four years before he directed again.

In hindsight, some of this bad luck may have been good luck. To Eric Roth, the departure of George C. Scott was especially regrettable because of the age difference between Scott and the actor who replaced him. "The guy who ended up playing the character really was younger than the part called for: the young actor Jason Miller, who was in The Exorcist, and who was also a playwright; he won the Pulitzer Prize for That Championship Season," Roth said. Yet Miller's relative youth—he turned 35 in 1974—gives his character an altogether sadder dimension than if Scott, who was 12 years older than Miller, had played the part. He possesses an energy and a competency that make his plight seem less than inevitable; his jet-black hair and tightly wound manner suggest a sprightly Ara Parseghian, not a gangster in decline. (I make the comparison advisedly: Miller would later play the former Notre Dame football coach in a motion picture.)

In that first scene, Cooper is kept awake by a vision of an empty row of warehouses. He will have jurisdiction over the warehouses (which are to store stolen property), but first he has to close the deal, and things are not going according to plan. To lie awake at night at 47 is pathetic, but at 35 it is tragic. "I pictured an older, bigger guy," a character says on meeting Cooper, as if speaking for the audience. (Was the line added after Miller was cast?) He seems to have too much going for him to be banking his future on dumb luck, but as his world begins to unravel that is exactly what he does. As he walks to his office on a dusty Los Angeles side street, he is accosted by a street peddler. He doesn't go for the timepieces and knickknacks that the guy is hawking, but something else gets his attention. "I know what today needs," the street peddler says. "Today needs good luck pieces." Cooper tosses the rabbit's foot in his hand and takes it with him.

In his great Film Comment essay on Mulligan's The Stalking Moon, Kent Jones rightly observed that "there are lengthy passages in many of [Mulligan's] films...during which you can turn off the sound and follow the action without any diminution of clarity or impact." In the case of The Nickel Ride, however, to turn off the sound would diminish not only its clarity and impact but also the counterpoint to Mulligan's grim images provided by Roth's jaunty dialogue. In this film, everyone has a nickname, and when they speak, it is usually in euphemisms. The warehouses Cooper is agonizing over are referred to as "the block," as when Carl (John Hillerman), Cooper's slick superior, tells him, "The block is your baby." Cooper is called "Coop" or "Key Man," the latter referring to the dangling set of keys he carries with him everywhere. Because Cooper's naïve, pretty girlfriend Sarah (Linda Haynes) is from the South, he calls her "Georgia." When New York Times critic Nora Sayre complained that the film was so confusing that it "resists an earthling's comprehension," I think she was thrown off less by the plot than by Roth's jazzy lingo.

For most of the film, a corn-fed cowboy named Turner (Bo Hopkins)—new to the L.A. crime world, fresh from Tulsa—is the personification of Cooper's dread. He fears Turner has been recruited to supplant him or kill him. At one point, Cooper and Sarah travel to a small cottage he has in northern California, ostensibly to finalize the deal for the block with a crooked cop (who never shows), and while there he has a terrible fever dream. He imagines that Turner shows up at the cottage unannounced with his rifle. (The invasion of private spaces is one of the film's obsessions—early on, Cooper chastises a thug for waiting at his desk before Cooper has arrived.) Assuming Turner to have bad intentions, Cooper grabs his own rifle and a struggle ensues between the two men. But Turner wrests the weapon from Cooper and shoots Sarah. In the dream, Cooper crouches beside Sarah's body and he screams into her ear, which surprises us. It's as if he feels her soul is receding inside her head and he must yell louder and louder for her to hear him.

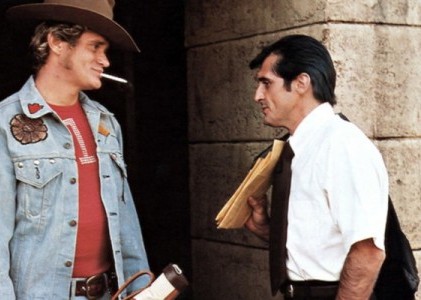

Bo Hopkins and Jason Miller in The Nickel Ride

Cooper's obsession with Turner causes him to underestimate the ill motives of the more polished Carl. In the penultimate scene, Carl reassures Cooper that he is safe despite the problems with the block, but does Cooper stop to remember that he, too, made promises that couldn't be kept? Early in the film, a sad middle-aged crook named Paulie (Lou Frizzell) comes to Cooper after he was unable to persuade a boxer (Mark Gordon) to throw a fight. Paulie cries, "The silly son of a bitch wouldn't sit down." Cooper tells him, "The tears are for nothing. No one's gonna touch you." But Paulie is killed, much to Cooper's rage. This should have been Cooper's clue, yet Jason Miller's vigor brings out the character's vanity. For all of his dread, it is a long time before Cooper really believes that his number is up. When Turner first meets Cooper, he says, "Hell, there you are, Mr. Cooper, up there with the greats. Babe Ruth, Marciano, John L. Sullivan, and Key Man"—an outlandish statement, but Cooper seems to almost buy it.

In the film Mulligan and Alan J. Pakula made of To Kill a Mockingbird, the father is unambiguously heroic. This may have been unavoidable. Who could put chinks in the armor of Atticus Finch? But the fathers in several films Mulligan made after his partnership with Pakula are capable of unexpectedly brutal acts. Cooper is a kind of father figure to Sarah; if Jason Miller seems young when compared to George C. Scott, Linda Haynes seems younger still when compared to Jason Miller. The trust she places in him is sweet—the way Haynes bites her lower lip after she asks him for some spending money—but misplaced. She is too credulous when he promises late in the film that the two of them will go to Las Vegas after his "business" is taken care of. But when she stands up to him and insists that he tell[s] her what is going on, why he has become so suspicious of everyone and everything, he lashes out and hits her. It anticipates the shocking scene in Mulligan's final film, The Man in the Moon, when the father played by Sam Waterston strikes his daughter out of fear (the daughter's actions have inadvertently contributed to her mother being hospitalized). In many ways, Mulligan was no sentimentalist.

Jason Miller and Linda Haynes in The Nickel Ride

For several years before his death in 2008, I tried to persuade Robert Mulligan to talk to me. I felt I came close. When I first sent an interview request in care of his agent, the answer was "no" but a message from Mulligan was relayed to me by the young woman handling my request. She said something like, "Mr. Mulligan says that you seem to be a sincere and serious young man, but he just doesn't do interviews anymore." I took this as reason enough to persist, so I found a way to contact Mulligan directly. We began a tentative correspondence, but he made it clear that he really didn't want to talk to me about his movies. I kept trying, but after my last letter he stopped answering. At least I have two beautifully written, if rather gruff letters to show for my efforts.

I now feel that Mulligan's best films speak as quietly as he did. When the characters stop talking in The Nickel Ride, the quiet is almost overwhelming. Jordan Cronenweth's photography is quiet, too, a real change of pace from the whirling camerawork Mulligan preferred in Summer of '42 and The Other. Nora Sayre wrote that "the numerous close-ups manage to stress the slowness of the action," but the slowness is hypnotic, like waiting for a Polaroid to develop. The score composed by Dave Grusin is so unlike the gorgeous ostentation of the scores of To Kill a Mockingbird or Summer of '42. You can hear a pin drop in The Nickel Ride, but it isn't a pin—it's a set of keys. ![]()

LATEST ARTICLES

-20140814-173707-thumb3.jpg)

Fighting Words

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 12, 2014

Fighting Words, Part 2

by Imogen Sara Smith

posted August 20, 2014

On the Margins: The Fil…

by Andrew Chan

posted August 12, 2014

Robin Williams: A Sense…

by David Schwartz

posted August 12, 2014

Key Man Agonistes

Key Man Agonistes

THE AUTHOR

Peter Tonguette is the author of The Films of James Bridges and Orson Welles Remembered. He is presently writing a critical study of Peter Bogdanovich for the University Press of Kentucky and editing a collection of interviews with Bogdanovich for the University Press of Mississippi.

More articles by Peter Tonguette